War Stories by Lyle Hansen.

Section 1.

Copyright 2002

My short

career in the Navy began in late winter of 1944 at the

At the

We were given a battery of tests to determine where we might best fit into the Navy. Rumors were that if you had worked at a specific trade or occupation, you would most likely be given something completely different. My test scores were good, and during my interview I was told I could qualify for the V12 program where college students could finish their education and become commissioned officers upon completion. There was just one problem, I could not be married! My wife and I had been married more than two years and we had a son about eight months old when I was drafted. I had no desire to divorce! I was assigned to the Naval Training School of Photography at Pensacola, Florida. Needless to say, I was very pleased to go to Pensacola after the end of my boot camp leave.

The men from Farragut being assigned to the Photo School traveled by train to Florida. We were in compartment cars done in green mohair upholstery and apparently built during the later part of the 19th century. The trip took a full week. We seemed to get sidetracked each time a fast freight needed the tracks. The train was powered by a steam locomotive, so by the time we arrived at Pensacola the white stripping on our uniforms was so full of soot it was hardly visible! It was near the end of May, and Pensacola was already hot. It was a shock coming from an area where remnants of snowdrifts existed only a week before. The white sandy beaches were very inviting, but highly reflective of the hot sun. A friend, Frank Grits, (a Cherokee from Oklahoma, who later lost a leg on the USS Franklin) and I spent the afternoon of our first liberty at the beach and I got the worst sunburn of my life.

The four-month session at the Photo School was divided into four concentrated courses of one month each. Beginning with basic still photography, processing and printing, it continued with aerial photography, mapping, and motion pictures. During the last two months we were going on aerial photography training flights several times each week. Two of those flights are quite memorable to me. On one of them I had to use a large mapping camera, hand held, from the rear seat of single engine trainer. It was necessary to stand up in the open cockpit to operate the camera. There was a gunner's belt to keep you secured to the aircraft. I had failed to notice that the spring clip holding the ripcord D-ring on my parachute harness was broken. Each time I stood up to use the heavy camera, the ring fell out and I would put it back in. When we had finished photographing the last target, and I sat down, I found the parachute had opened and there was white nylon all over beneath me! I called the pilot on the intercom to let him know. He called for an emergency landing at North Field. If the 'chute had escaped from the cockpit, it might have been a real disaster. As it was, I was given a ride back to the parachute locker at the main field in the back of a pick-up truck driven by a Wave while I held down the big pile of nylon. The chief in charge at the parachute locker felt I had broken the spring clip. I'm sure it was his responsibility to see that no defective parachutes were issued, but I suppose I should have inspected it more carefully myself when I got it! He had me write out a two-page report before I was released. The second incident was on a training flight in a Beech twin-engined airplane. We were to go to Pearl River, near New Orleans, to do some mapping. We were west of Mobile, Alabama, flying at about 1500ft. There were small puffy clouds just above, which made for a bumpy ride. Suddenly, with no warning, both engines stopped. We began a rapid descent at a steep angle. I could see the pilot and copilot frantically throwing switches, and working a wobble pump. Fortunately, just as we were about to crash into the pine trees, the engines fired and we came out of the dive. Switching fuel tanks seemed to have fixed the problem, so we continued on, but climbed to ten thousand feet! On the return flight, with the fuel running low, we landed at Biloxi, Mississippi, for refueling. Just as we taxied up to the fueling area, both engines quit again! The moisture in warm humid air in partly empty tanks at sea level condenses at cool higher altitudes leaving water in the fuel tanks! It seemed that the ground crews had not checked or drained the condensed water often enough.

At the end of our second month of photo school, all seamen 2nds were given the exams for promotion to Seaman 1st class. I don't recall anyone who didn't pass. At about the same time, my wife, Marie, came down from Seattle to join me. Our infant son stayed with my parents. The majority of our graduating class at the end of September went on to aerial gunnery school at Jacksonville, Fla., to become qualified air crewmen. But those of us who were not perfect physically were disqualified. I was slightly near-sighted, and wore corrective glasses. All graduates were rated as 3rd Class Photographer's Mates. (We had Marines at the school too, but I don't recall what kind of promotion they received.) Those not going to Jacksonville went to Anacostia, D.C. Naval Air Station to the Photo Science Lab for six weeks further training. Fortunately, Marie was able to come up there as well. She found office work at the Marine Corps Leatherneck Magazine. We had a room in a large old home out in Chevy Chase and I was able to be with her whenever I had liberty. It was a great experience to be in Washington D.C. We were able to visit the Smithsonian, the library of congress, the capitol building, the Washington monument, the then new Jefferson memorial, the national art gallery, and looked through the fence at the White House. One Sunday we took a bus out to Alexandria and visited nearby Mt. Vernon. The training at PSL was in photolithography, and it appeared that we were now destined to become printers. We learned to make half-tone negatives on process cameras, (much like the photo template camera I had worked with at Boeing, but smaller and not as precise) and to operate a couple of different types of offset printing presses. Around mid-November our group completed the classes and we were assigned to San Diego's North Island Naval air Station. Marie stayed in D.C. another week or two to earn enough money for her train fare back to Seattle.

After arriving in Los Angeles three or four days later, we left the "cattle car" train and boarded a streamlined train, the "San Diegan", for a smooth but short trip down the coast to San Diego and were ferried across the bay to North Island Naval Air Station. We were assigned to temporary duty there while waiting to ship out. World War II had been going on for almost three years, and no one was predicting it would be over soon.

I enjoyed San Diego and felt more at home there than I had in Florida or Washington D.C. However, the stay was short. About a week before Christmas, my name, along with about 50 others appeared on a list on the barracks bulletin board. We were to report to “CINCPAC”. What was that? We learned it was navy jargon for Commander-in-Chief Pacific, then located at Pearl Harbor. We had not the slightest idea what lay in store. The general assumption was that we would be assigned to various air groups from there, probably to splash hypo for a lot of photographers more senior in the service than we. Liberty was cancelled. Letters were written home with a new return address: “Fleet Post Office, San Francisco.” From then on, every letter was censored before it was mailed.

A couple of days later we boarded a small aircraft carrier moored with several others at North Island. These were the so-called “jeep”, or escort carriers, slower and much smaller than first-line carriers in the Essex class. In this instance they were used to ferry aircraft and personnel out to the Pacific fleet. Both flight and hangar decks were packed with brand-new Hellcat fighters, and I don’t recall any unassigned bunks. The ships left the harbor and formed a convoy with a screen of destroyers and planes on patrol overhead. The convoy’s zig-zag path across the Pacific was meant to confuse enemy subs. Large tubs of blue dye were set up on the flight deck and we were ordered to bring out all our white hats to be dyed a deep ocean blue. All ships were camouflage painted, and the idea was that no cluster of white hats should spoil the effect! Passengers in transit, regardless of ratings, were assigned to chipping paint and general cleanup duties. Each day, the weather grew warmer, and when we came within range of airfields on Oahu, the planes were launched. First from catapults, and when there was room enough, the rest took off from the flight deck. Elevators raised those stored on the hangar deck, and soon all the planes were gone.

Later that day, when the islands were sighted, an announcement was made that we would be having a Waikiki Christmas. The lush green of Oahu with its mountain backdrop partly covered with puffy cloud formations was a beautiful sight after a week of little to see except the dark blue of deep ocean water. We entered Pearl Harbor on Christmas Eve and moved ashore to a tent city set up in the edge of a sugar cane field. This was at Aiea, at the edge of Pearl Harbor. When I visited the area some ten years ago the sugar cane was long gone, replaced with shopping malls and apartment houses. While we didn’t get to spend Christmas at the beach, we did get to see it on a ride around the island in military trucks. The island was very crowded with thousands of men from all branches of the service. It was interesting to see that every military installation seemed to have been hit during the Japanese attacks. The damage appeared to have been much more extensive than we had been led to believe at home. The following day we went by truck to a landing where we boarded a motorboat and were ferried to Ford Island. Along the way we passed over the sunken battleship Arizona, a grim reminder of why we were there. Thick black oil still coated the shoreline and rocks on the beach three years after the attack. Admiral Nimitz’s CINCPAC headquarters was on Ford Island. We were led into a large auditorium where an officer welcomed us and explained our assignment. We had been selected as combat photographers attached to the Admiral’s staff and would be expected to take part in all the upcoming actions of the war. We were warned that it would be dangerous work and that if anyone felt such duty was not to his liking, to stand up for reassignment elsewhere. “Maybe even here in Hawaii” the officer said. I think most of us felt that if we did stand up, we probably would be given much worse duty! Only two were brave enough to stand and ask for a different assignment. Wonder of wonders, we later learned they both stayed on Oahu for the rest of the war. We were shown the film “Fighting Lady”, soon to be released to the public. It depicted life aboard an aircraft carrier and contained considerable footage of recent action in the Pacific. It had been filmed under the direction of Commander Dwight Long, then an officer in charge of one of the combat photo units. It was interesting to me that Dwight Long was here. When I was in high school in Seattle, I had read articles he sent for publication in the old Seattle Star newspaper. He had built a sailboat in Seattle and sailed it around the world, with lectures and the newspaper articles paying his way. I had enjoyed reading of his adventures, and after his boat was wrecked in a hurricane on the east coast, he came back to Seattle giving lectures to raise money for repairs. My older brother Don was at the time working as a doorman at the Blue Mouse theater, and had driven Long to his parents home after one of the lectures. I therefor felt I had something in common with him, but when he called me in to be interviewed for a possible assignment and I learned his next project was to be a film like Fighting Lady, only about submarines, I didn’t pursue it. Knowing he wanted movies, I indicated that I really preferred doing stills. We had a pleasant conversation about Seattle and I never had to go out on a submarine war patrol. (The flamingo pink Royal Hawaiian Hotel at Waikiki was used by submarine crews resting up between war patrols. I visited there and marveled at the huge banyan tree in the courtyard. It hadn’t changed much when I last visited the Islands, but their clientele had!)

I was assigned to Combat Photo

Unit #6. We were nine enlisted men under the command of Lt. JG. Gerald Rogers.

We were each issued a variety of brand-new camera equipment, marine corps green

fatigue clothing, a bowie knife and a Colt 45 automatic pistol.

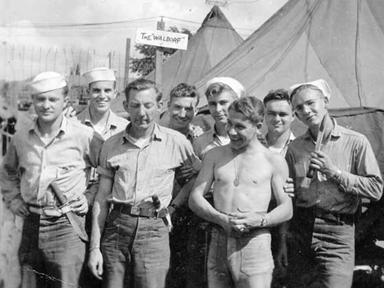

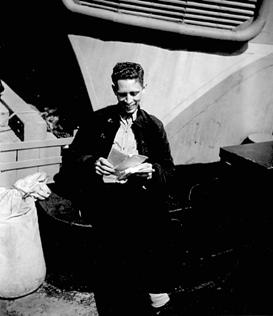

The picture on the left shows eight men from one of the tents in "tent

city". I am the one on the left end.

For about a week we had various training assignments such as documenting

the unloading of cargo ships at the Honolulu docks. Then, in early January, we went out on

maneuvers with the marines. Simulated

assault landings were scheduled on the steep volcanic beaches at Maui. I found myself the lone photographer on a

troop transport loaded with about five thousand marines of the fifth

division. They had been aboard ship

since leaving the states. Their only chance to set foot on dry land was to

climb down cargo nets rigged on the sides of the ship and storm the beach from

assault craft while navy guns fired over them. I had no idea where these

marines were headed, but some seemed sure their target would be Iwo Jima. If they knew for certain, that could be the

reason they hadn’t been allowed to go ashore!

As is normal with servicemen, conversation often centers about home

towns, with each participant extolling the virtues of his favorite place in the

world. I did my best to hold up Seattle

as my favorite to a small group of four or five. When the discussion ended, another marine who

had stood on the sidelines came up and spoke to me. His name was Bill Keillior, he was older than

most, and was from Seattle. He told me

he had been working in Alaska doing construction work for the first part of the

war, but had decided that he wanted a more active part, so had joined the

marines. His wife was Mildred Alley, who

had a dance studio near the U of W campus.

He was interested in me not only because of Seattle but also photography.

He had done newsreel photography before the war, had been in China when the

Japanese went into Nanking, also had covered a revolution in South

America. His job with the marines was

driving a bulldozer that was now stored in the cargo hold. The bulldozer was to

remove tank traps immediately before a landing.

The picture on the left shows eight men from one of the tents in "tent

city". I am the one on the left end.

For about a week we had various training assignments such as documenting

the unloading of cargo ships at the Honolulu docks. Then, in early January, we went out on

maneuvers with the marines. Simulated

assault landings were scheduled on the steep volcanic beaches at Maui. I found myself the lone photographer on a

troop transport loaded with about five thousand marines of the fifth

division. They had been aboard ship

since leaving the states. Their only chance to set foot on dry land was to

climb down cargo nets rigged on the sides of the ship and storm the beach from

assault craft while navy guns fired over them. I had no idea where these

marines were headed, but some seemed sure their target would be Iwo Jima. If they knew for certain, that could be the

reason they hadn’t been allowed to go ashore!

As is normal with servicemen, conversation often centers about home

towns, with each participant extolling the virtues of his favorite place in the

world. I did my best to hold up Seattle

as my favorite to a small group of four or five. When the discussion ended, another marine who

had stood on the sidelines came up and spoke to me. His name was Bill Keillior, he was older than

most, and was from Seattle. He told me

he had been working in Alaska doing construction work for the first part of the

war, but had decided that he wanted a more active part, so had joined the

marines. His wife was Mildred Alley, who

had a dance studio near the U of W campus.

He was interested in me not only because of Seattle but also photography.

He had done newsreel photography before the war, had been in China when the

Japanese went into Nanking, also had covered a revolution in South

America. His job with the marines was

driving a bulldozer that was now stored in the cargo hold. The bulldozer was to

remove tank traps immediately before a landing.

I had understood that my

assignment to this ship was intended to be only for the training exercise. But,

as I prepared to leave the ship when it tied up again in Honolulu, I found that

a different interpretation of my orders had been made. It seemed I was to

remain with the marines for the entire operation, not just the maneuvers. I was

allowed to request a clarification of the orders, a radiogram was sent to

CINCPAC, and it was determined that I was indeed supposed to leave the ship and report back to CINCPAC. When I said goodbye to Bill Keillior, he told

me, “if you see me on the beach, don’t step on my face.” It seemed a strange

remark, until later when I learned what happened to the men of the fifth

division. Kiellior did survive, one of

only three men left from his company of sixty. One had no legs, one was, I

believe, blinded along with loss of an arm, and Bill had been the target of a

mortar round which landed directly in front of him, D-day plus 12. He told me he was knocked unconscious, awoke

many hours later aboard a hospital ship, badly wounded in the stomach, and

unable to speak or see for several days. When I saw him in Seattle two years

later, he still had trouble with his stomach and spoke with a slight stutter.

Of course at the time of his strange remark to me, Iwo was still ahead, and I

wasn’t acquainted with war.

One of my Pensacola classmates, McGrath, whose combat photo unit had

drawn duty with the amphibious group, was assigned to an LCI modified for

launching rockets. He had been on it

during the practice assaults at Maui and was very apprehensive about his

assignment. He told me he thought he

wouldn't survive. He bought a shoulder

holster for his pistol in Honolulu after the maneuvers. He seemed to have a premonition of death,

which I just didn't believe.

Back on Oahu, instead of the overcrowded tent city, I was billeted at the YMCA, sharing a room with two other photographers. One was Leif Erickson, who had been one of my instructors at Pensacola. He had been an actor in Hollywood. One of the films he had acted in was the prewar technicolor version of Robin Hood. He had also been a cameraman for Republic Studios and carried a union card in the Hollywood Motion picture photographer’s guild. The other man was a tall good-looking fellow from Hollywood, whom I had first met as we left Farragut boot camp in Idaho going on the train to Pensacola. I don’t know much about his background, except that he was aspiring to be an actor and had been an extra in some films. He could tap-dance. How he came to be a navy photographer, I never understood. When doing class assignments at Pensacola, he would bring a film holder out where a classmate was setup on assignment and ask the fellow already set up to expose his film for him. Then he would take the holder to the darkroom and buttonhole someone about to begin processing and ask to have his film added to the batch while he went to get a coke for them both. The polite name for people like this was goldbrick. Some other terms that came to mind seemed more apt at the time. He also had a way with the girls, for instance, when our train stopped for a few hours in St. Louis on the way to Florida, there was a girl who came aboard with him and seemed to think she should come along. Months later on the long trip from D.C. to San Diego we had a ten-hour layover in New Orleans. Most of us spent the time sightseeing in the French quarter and gathered at the Court of the Two Sisters restaurant in the evening before we were due back at the train station. Our aforementioned friend wasn’t there. Someone asked, “Where’s Joe?” Someone else volunteered that he saw him in the early afternoon driving down Canal Street in a red convertible with a blonde. At train time, no Joe. Someone else mentioned that as everyone was leaving the train depot, Joe stayed behind, talking with the stationmaster. The train pulled out without him, but it only moved out across the river and halted there for about an hour. Then, just before departure, a red convertible pulled up and the blonde put Joe on the train. I was a witness to the way things caught up with him while we were rooming at the YMCA in Honolulu. One afternoon when I returned to the room there was a message for me. I was to call the Naval Hospital and speak to Joe. The person answering the phone said “Venereal Ward” and put me though to Joe. He gave me the combination to his locker and asked me to please look in his little address book for the address of a certain waitress in San Diego. He said his doctor wanted to get in touch with her, very important. We were scheduled to leave Honolulu a few days later, but Joe couldn’t go, as he was confined to the hospital. More about Joe later. (Joe wasn't his real name.)

While billeted at the YMCA our

duty station was Kodak Hawaii, on Kapiolani Blvd., out toward Waikiki, but

within walking distance of the “Y”. Kodachrome film was processed there and I

was quite interested in watching the process, as I had only read about it

before.

Near the end of January, we went

back to Pearl Harbor, this time to go to sea.

Combat Photo Unit #6 was assigned to the Fast Carrier Task Force. We went aboard the USS Bennington, a new

Essex class carrier, and departed Hawaii for Ulithi Atoll, about 4000 miles

away in the western Carolines. Ulithi is near the international date line, at

the edge of the Philippine Sea, and about ten degrees north of the

equator. We had use of one of the

carrier’s ready rooms while we were in transit.

Ready rooms were usually used by flight personnel just prior to take-off

and were located just below the flight deck. This was also our general quarters

station. Mr. Rogers gave us briefings

there and told us what he knew of our assignment. We still didn’t know where the next operation

would take place. Guam, Saipan and Tinian had recently been taken. The

Philippine liberation had begun just three months before and still continued.

I don’t recall all the ships that

sailed with the Bennington to Ulithi. There were several new carriers, a couple

of cruisers, and destroyers. I believe

there were no battleships along.

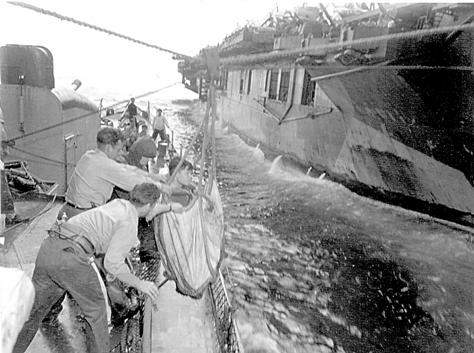

Cruising nearly 4,000 miles, the destroyers had to be refueled underway.

This was accomplished by coming in close alongside an aircraft carrier or other

large ship. A light line fastened to a

projectile was fired across to the smaller ship and successively heavier lines

were pulled over until the heavy fuel lines could be hauled across and

connected. Then the fuel was transferred without change in speed or

direction. Watching this operation I was

amused to see a sailor on a destroyer’s aft deck sitting on a stool while

another sailor gave him a haircut. There

was enough of a sea running so that the destroyer was taking water over the

bow. The pitching and rolling of the

slender ship caused the water to run down the decks and aft so that it neatly

washed the hair clippings overboard!

Fighter aircraft from the carriers patrolled above the group, searching

for possible enemy ships. When we passed within striking distance of Truk, air

raids were conducted from the carriers in our group against that large Japanese

naval base. It was called a practice

mission, but was complete with return anti-aircraft fire!

Ulithi had been taken about 90 days before,

without resistance. It is a large coral

atoll, about forty miles long and twenty miles wide. Inside the ring of low

coconut-palmed islands a huge force of ships was gathering. I have since read

that it was the largest gathering of naval forces in existence before or since.

There were at least twenty Essex class carriers, as well as the Saratoga and

the light carriers San Jacinto and Belleau Wood. The newer battleships, the

Iowa, Missouri, South Dakota, Washington, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Indiana, and

Alabama were there. These ships grouped with cruisers and destroyers formed the

fast carrier task force. At the other end of the anchorage inside the lagoon

were the amphibious forces, some of the older battleships and various support

vessels. Troop transports, including the

one I had been on at Maui, having left ahead of us, were there along with many

LCI’s (landing craft, infantry) and LST’s. (landing ship, tank) Of course my

friend McGrath was there on the rocket launcher, but I didn't see him.

At night the whole lagoon was

lighted by the lights of the ships at anchor.

There was no attempt at blackout, since the area was considered out of

range for the enemy. I don’t recall if

it was the night we arrived or if was a night or two later, but we were

startled by a tremendous explosion, all lights went out and everyone went to

general quarters. The Bennington was not

hit, but a sister ship anchored a short distance away, the Randolph, had been

the target of a Kamikaze. The explosion shook the ship violently even though we

were probably nearly a mile away. Reverberating inside like a drum, it was

deafening. Running to the ready room while the GQ gongs were sounding, I was

barking my shins at every bulkhead door, since all lights were now out. Just

before I reached the ready room I collided with someone running in the opposite

direction. We were both knocked down, our helmeted heads making another loud

noise. Once inside, where most of CPU #6 was already gathered, we were soon

joined by Mr. Rogers. He said that he

had really bumped his head running into someone out in the passageway! I had

knocked down my own CO but he never held it against me. The confusion and

excitement of the surprise attack settled down, and we found out what had

happened. The Randolph had been hit in

the stern and the explosion started a fire. More explosions followed as heat

from the flames set off ammunition. The damage control crew soon controlled the

fire, and we learned loss of life was low, since the hit was in the stern of

the ship and few crewmen were there at the time. A movie was being shown at the forward end of

the hangar deck and most of the men not on duty were watching the film. The

Randolph had to be repaired before it would be fit for battle. Speculation was that the suicide crew (it

wasn’t a lone pilot) had come from either Yap or Truk. Yap being more likely since it was closer. At

Ulithi the fleet was under the protection of Army Air Corps radar and fighters,

since carrier aircraft could not operate while the ships were at anchor. Because of this, the ship’s radars were not

operating. We never knew if the attacker

came in too low to be detected by the Air Corps radar or if they just didn’t do

their job. Interservice rivalry tended

to believe the later, but I suspect it simply flew too close to the water to be

detected in time for a warning.

We still had not been told where

the next operation would take place. But

we were given our assignments. I was to

be on a destroyer, the USS McKee. Two of

the nine men in our unit were to stay on the Bennington with our officer. He delivered the rest of us to our various

assigned ships by motorboat on the day we were to depart Ulithi. As we passed

beneath the stern of one of the aircraft carriers, there was a sailor up there

frantically waving his hat and shouting at us.

Remember Joe, who missed shipping out from Honolulu because he was in

the hospital? After he was released from the hospital, he came by air transport

to rejoin his unit at Ulithi.

The Bennington

and the McKee. (Taken from the Belleau

Wood in April 1945 during the Okinawa operation.)

The McKee was

anchored the farthest from the others, so I was the last to reach my new ship.

I climbed partway up the steel ladder on its starboard side while Mr. Rogers

passed up the camera equipment, film and my personal gear. Then I could heave

them over my head to the deck of the destroyer.

The motorboat’s gunwale was riding up and down against the lower part of

this ladder with the wave motion.

Suddenly a much bigger wave carried the boat several feet higher. I

tried to scurry up the ladder, but wasn’t fast enough. My left leg was pinned between a steel rung

of the ladder and the motorboat's gunwale about six inches above my ankle. For a brief instant I thought the leg was cut

off, but I was able to climb on up to the deck and found I could stand on it.

Mr. Rogers seemed quite concerned and wanted to make sure I was O.K. before he

returned to the Bennington. There was a

doctor on board, and he dusted sulfa powder where the skin was broken, checked

for broken bones and put on a bandage.

There were a lot of broken blood vessels and swelling began immediately,

but no broken bones, so I could walk and carry out my duties. I got my

equipment stored, film into the ship’s frozen food storage and was given a bunk

directly over the screws on the starboard side of the ship. Late that afternoon, we put to sea under a

dark gray sky, and outside the lagoon the seas were running high. The motion of the destroyer was different

than anything I had experienced before. The skipper announced that we were

going to Iwo Jima. My leg was throbbing and was quite swollen. That night, probably from the combination of

everything, I became seasick. As the

ship rode the swells, the screws would occasionally break above the surface of

the water pounding hard and vibrating loudly in sleeping quarters. It was the first and only time I was truly

seasick, and washing my vomit from the rolling compartment floor made me no

less miserable. (It was tradition that those making a mess had to clean it

up.) I usually felt a little queasy the

first two or three days out, but except for that one occasion, I didn’t suffer

from seasickness. On the destroyer I often stood on the bow

enjoying the almost roller coaster effect of moderately heavy swells.

The USS McKee,

DD575

.

There

were times, in heavy weather, when the destroyer seemed more like a submarine.

Anyone who went out on deck would have been washed overboard. I met an

electrician who was chronically seasick. He become ill whenever he went below

deck and always felt sick while the ship was in motion. The cooks would give him sandwiches through a

porthole from the galley so that he didn’t have to down to the mess deck. He had been on the ship for three years, and

constantly lost weight while at sea.

Back in port, he would begin to gain it back. He had tried to get a

transfer to shore duty and when that was denied, to some larger ship. All to no avail, but a concession was to give

him the job of running the battery shack. It was on deck where he could see the

horizon, and that helped a little.

McKee crewman

standing watch in the forward gun mount.

As combat photographers our orders from CINCPAC specified that we were not to stand watches. This would have prevented us from doing photo work during action, and that was why we were there. In the time between actions we made pictures of the men going about their duties and documenting activities wherever we were. These pictures were sent to hometown newspapers as a navy public relations effort with the folks at home. On the McKee I kept busy documenting everything I saw and tried to get a picture of each of the crew members as they did their jobs. The smaller ship seemed to have a more relaxed attitude toward the stiff regulations on larger ships. Everyone knew each other, and this made the term shipmate more meaningful. I was surprised to find flying fish on deck some mornings. They would glide aboard by accident at night while we were in the tropics. My leg improved as the days went by, the pain had subsided, but it was numb where it had been smashed against the ladder. The doctor said it was probably due to nerve damage and that the swelling would gradually go away. The dressing was changed every few days. As we moved north the weather changed. The warm air was gone and it became quite chilly. From time to time the destroyer would have picket duty and be over the horizon out ahead of the other ships. The ship's top speed was 45 knots, equal to about 50 miles an hour, but seldom went that fast. At 45 knots the fantail was awash, and vibration was felt all over the ship. Crew members said the shaft bearings needed to be replaced. Three years in the Pacific created a lot of wear. The carrier aircraft maintained constant combat air patrols as we continued north. The task force moved up to Japan’s coast and our aircraft struck the Tokyo area and various airfields to eliminate as many of the enemy’s aircraft as possible, hoping to keep them from interfering with the landings soon to take place at Iwo. The weather turned so cold that planes were taking off from icy flight decks.

40mm guncrew

standing watch on the McKee. Bitter cold eighty miles off the

coast of Japan during the Iwo Jima operation. February, 1945

On the McKee there was constant vigilance as we performed screening duties for the task force. Whenever the radar detected enemy planes the general quarters gong would sound and I would climb to my battle station on a platform near the top of the aft stack to wait for action my cameras could record. The fast carrier task force was divided into several groups, each with several carriers, one or more battleships, cruisers and the usual screening destroyers. Operating between Japan and Iwo, it protected the invading force from aerial attacks emanating from Japan, and also supported the invasion with direct air support to the Marines on the ground. One evening, just after the invasion began, aircraft coming from Japan headed for Iwo. As we watched, the night sky was lighted up just over our horizon by several large explosions. The brilliance quickly faded, replaced by a dull glow and when that faded out our ship soon secured from GQ. We learned that the Saratoga in another battle group had been hit by a flight of several suicide planes and was too badly damaged to stay in action. Another of my photographer acquaintances was manning his battle station high on the island superstructure when the Kamikazes hit. Telling me about it later at Guam, he said he had jumped from his perch, rode down the signal flag halyards and ended up in the flag locker below! The Saratoga was our only remaining pre-war carrier and this was her last battle. Repaired later at Pearl Harbor, she was converted to carry personnel home after the end of the war. I rode on the “Sara” from Pearl to San Francisco when I returned to the states. Traveling at flank speed, it took only three days and two nights. Later she served as a target at Bikini in the atomic bomb tests.

View from my battle station on the

McKee’s aft stack. 60 miles off the

coast of Japan, February, 1945.

Our battle group fared well during the Iwo operation. One Japanese fighter got past our combat air patrols but was shot down by the screen of destroyers. The McKee’s guns fired, but the target was too far away, and one of the other ships made the hit. My pictures showed only black puffs of smoke from the exploding anti-aircraft fire. The sharp reports from our five-inch guns echoed inside my helmet and made my ears ring. The wads of cotton we were given weren’t very effective! Once a floating mine was found in the task force’s path and one of the McKee’s sister ships, the De Haven, was firing at it as we steamed on past. We stayed near Japan until some time in March, when I took pictures of happy crew members opening their Christmas mail.

Christmas Mail arrives on the McKee! Off the Japanese coast in March, mail

from home was very welcome. Never mind that it was about three months in

getting there. A V-mail system was

developed (the V stood for Victory) It involved microfilming the letters,

sending the film to a central point near its destination and then printing

out and distributing copies.

Whatever form it came in, mail was always welcome.

Christmas mail arrives on the

McKee in March.

It may be interesting to note that we operated both as task force 38 and 58. We hoped this was confusing to the enemy, making them think there were two giant task forces taking turns in their attacks against them. The ships and their crews didn’t change, only the admirals in command were different.

F4U Corsairs taking off from the Bennington's icy flight deck, bound for Tokyo.

Torpedoman on watch at the launch tubes talks with shipmate.

The battleship Indiana refueling

the McKee while underway with Task Force 58.

Rescued Marine Corps pilot being

returned to the Wasp in a mailbag during the Iwo operation March 1945.

The fast carrier task forces continued to raid the Japanese home islands and the Ryukus. During raids on Okinawa in March, The McKee picked up a downed Marine Corps pilot and brought him back to his squadron on the Wasp.

Bad weather hampered operations. A typhoon once overtook the task force. In heavy weather and low on fuel the McKee would roll a full 45 degrees to either side, hesitating as she righted herself, and capsizing became a real possibility. A destroyer with its narrow beam designed for speed tends to be top heavy from its guns, torpedoes, depth charges and other battle gear up on deck. Fuel in the tanks, helps as ballast under such extreme conditions. A few months before three destroyers had capsized near the Philippines in similar weather. Low fuel and increasingly heavy swells broadside to the ship created a dangerous problem for the skipper. He couldn’t change course to quarter into the giant waves because orders to maintain course and speed were vital and fueling at sea in that weather was not possible because of collision danger. Therefore he had decided to pump seawater into some of the fuel compartments to get the necessary ballast. Fortunately, an order for a change in course came just before this was done. It is difficult to say exactly how large the waves were, (some said 90 feet from trough to crest) they were very high, but I think they were probably no more than 50 or 60 feet. There was nowhere on the ship that was dry. It was impossible to be on deck because the waves breaking over the ship would have carried anything not bolted down over the side. Some of the large carriers had the overhanging corners of their flight decks bent down around their bows and catwalks along the sides of the flight decks were carried away. The force and weight of thousands of tons of seawater were slammed over the forward end of the flight decks as giant waves lifted sterns out of the water, forcing the bows under the oncoming waves. Huge steel I-beams bent as though they were matchsticks. The carrier flight decks were 70 feet above the sea surface. Admiral Halsey took the fleet through the typhoon’s eye hoping, I think, to find calmer seas there. This was true, and we actually saw the sun for a short time. While it was calmer, it was still stormy, and we had to cross through and go back into the higher winds and seas again. For a time, instead of using his nickname of “Bull” Halsey, some referred to him as “Typhoon” Halsey. I will try to describe really heavy weather in a destroyer by telling of two things: one was trying to sleep on a pipe frame bunk with the ship rolling and pitching to the extent that you either fell off or strapped yourself in while the propellers intermittently broke the surface of the water with a thrashing that sounded like thunder. The other was the complete bedlam that I saw once in the mess deck. The destroyer’s galley was located on the main deck, with the mess deck below. Food was carried down for serving. I think this is how the term “chow down” originated. After the cooks prepared the meal in the galley, the mess cooks took it, steaming hot, in large stainless steel rectangular kettles, with one man on each side as they went down the companionway ladder to the lower level. (The “ladder” was really what would be called stairs on land and companionway means it was a double set of stairs, one for going down and one for coming up.) The seas were running high, but a bosun had piped chow call over the announcing system, and it was time for the noon meal. About then we either changed course or there was a sudden change in the weather. Never one to miss a meal, I moved over the heaving deck toward the ladder. The folding tables and benches were set up below, and ahead of me two men were bringing a big kettle of beans down the ladder. Some food had already been served, and the servers were having a hard time keeping their balance. Then we hit a really big one, and the men spilled the beans! Cascading down the steps, the hot soupy beans made the steps and deck very slippery. Benches and tables came adrift and began sliding from one side of the mess compartment to the other. Some of the men became seasick and more food spilled from trays and serving tables. Each roll of the ship collapsed more tables and benches, creating havoc in the slimy mix of food and vomit. Struggling to keep their footing, those who had managed to not be sick, eventually secured the benches and tables without serious injury.

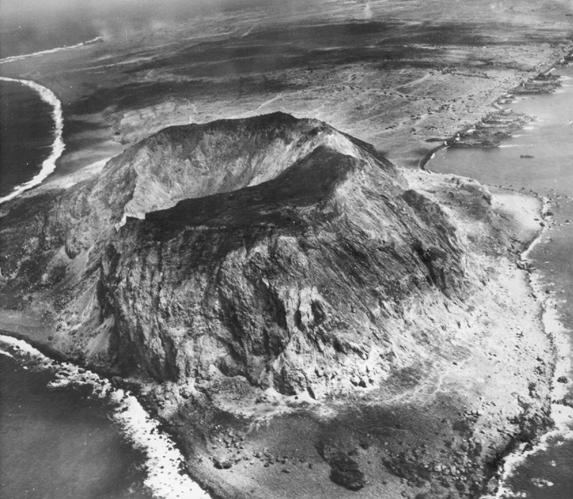

Iwo Jima beachhead with

Mt. Suribachi in the foreground. Taken shortly after the initial landings,

smoke from gunfire is visible in the upper portion. Official

US Navy Photo.

Iwo Jima was declared secure during March and part of the fleet withdrew to Ulithi to regroup and prepare for the next operation. CPU #6 members were reunited on the Bennington and Mr. Rogers flew to Guam to get our new orders. Up until that time I hadn’t really felt in serious danger. From what I had seen, the war was going fine. When the enemy got too close, he was shot down. Sure, the Saratoga got hit, but wasn’t sunk, and casualties were said to be low, so why worry? When Mr. Rogers came back few days later and briefed us it began to sink in. My good friend McGrath who had been assigned to the rocket launching LCI had been killed three days ahead of D-day at Iwo. They had pulled into shallow water to launch their rockets as a part of the softening up of the landing area. A mortar shell struck the LCI exploding its hazardous cargo in all directions before it had a chance to fire the rockets. McGrath and the others on board had all been killed, and there was little left of their vessel. Apparently the shallow water had been marked in a grid pattern with bamboo poles so that all that was needed was to set the mortar with the proper coordinates and the round would fall in the targeted square! This was a big shock to me, for McGrath was a close friend.

I had sent a copy of this photo to my brother in the army shortly after we had arrived in Honolulu. I am the one in the black trunks posing with a surfboard in front of the Royal Hawaiian at Wiakiki. An ordinance officer in Patton's 3rd Army, he received it during the Battle of the Bulge. I think he decided life wasn't fair! He told me later that I sounded very different in my next letter.

Iwo proved to be a very hard won victory, but was necessary to provide a landing place for B-29’s crippled in the raids on Japan and to gain a base for fighter planes affording some protection for the raiding B-29’s. The total US casualties were about 25,000, with about 6,000 marines and nearly 900 navy men dead. Casualties on the Normandy beachheads were considerably less than those on this tiny volcanic island. I think the number of Japanese defenders was about 25,000. Very few surrendered. Having Iwo, the B-29 raids became more effective, thereby shortening the war.

A tiny coral island at Ulithi named Mog Mog was designated as a recreation area. All ten members of CPU #6 went there on liberty after the Iwo operation. We found it to be nearly knee-deep with empty beer cans! No alcohol was allowed aboard ship, but here each man could buy two cans of Fort Pitt beer. A few coconut palms provided only a little shade from the tropical sun directly overhead. It was a relief to set foot on land for a couple of hours, but was certainly no one’s idea of a tropical island resort.

For the next operation, the invasion of Okinawa, my unit was again assigned to the fast carrier task force, and my next ship was the Belleau Wood, CVL 24. This was a light aircraft carrier of the Princeton class, which included the Princeton, the San Jacinto and the Belleau Wood. Originally designed as cruisers, they were converted to aircraft carriers while under construction before the war. They were smaller than the Essex class and unable to carry as many planes, but had the speed needed to operate with the fast carriers. The Princeton was lost in the Philippines during the battle of the Sibuyan Sea in October of l944. Ensign George Bush, later President, was shot down while piloting a torpedo bomber from the San Jacinto near Formosa. He was just 20 years old, even younger than many of our all quite young pilots. (Rescued by submarine, he was sent home on rotation before the Iwo Operation began. U. S. submarines rescued a total of 504 airmen down at sea during the war.)

Our stay at Ulithi was short, the ships were re-supplied and the fleet was soon on the move again. While Okinawa had been raided by our aircraft before, it was now hit by a force of our older battleships and amphibious assault forces that blasted the beach. The battleships were those repaired after they had been sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor. On Easter Sunday April 1, and my dad’s birthday, the marines and army troops were put ashore, and the battle for Okinawa began on the ground. Off shore with the fast carrier task force it was already in full swing. While our aircraft flew continual bombing and strafing missions to support the troops, we were under nearly constant attack or threat of attack by Kamikazes. Looking up statistics, I find that about 4000 suicide attacks took place during the war with Japan, and 3000 of these took place during the 11-week Okinawa operation. Historically, naval battles had always been a matter of striking the enemy as hard as possible, trying to destroy his ships while he tried to destroy yours, and then retiring to a base to repair and refit for the next action. Most naval battles lasted no more than a few hours. The rules had changed. Our fleet had come to stay.

An aircraft carrier was a

dangerous place even without its being the kamikaze’s target of choice. Bombs, torpedoes, rockets and ammunition were

stored close to thousands of gallons of aviation gasoline. Then there were the

aircraft propellers swinging on both the flight and hangar decks as engines

were checked or the planes taxied. The

unwary could easily walk into the deadly arc of a moving prop. The fumes and

noise of engines revving up on the hangar deck while the mechanics did their

work seemed a kind of organized bedlam.

When the Franklin was hit, one bomb penetrated into the hangar deck

where aircraft were being fueled and armed for flight. Intense flames of

burning gasoline set off secondary explosions of the bombs and rockets. In the tradition of good U.S. Navy

commanders, the captain did all he could to save the ship. By the time the fire was under control, nearly

one fourth of the crew members had died, many trapped by the flames without a

means of escape. There was no call to

abandon ship, but some did so to save themselves. The ship did not sink but

truly was a total loss. Another of my

Pensacola classmates was assigned to the Franklin’s photo lab. He lost a leg. I learned of this a couple of months later,

for all I could see at the time of the disaster was smoke coming up over the

horizon from the adjacent battle group. During one 24-hour period there were

350 kamikaze attacks against the task force.

A journalist who had covered part of the war in Europe and was now

writing about Okinawa wrote, “There are no foxholes aboard ship.” Altogether, 4,900 navy men died on their

ships during the entire battle for Okinawa.

Most of these were on the smaller ships, 32 were sunk, 368 damaged. In the fast carrier task force, nothing

larger than a destroyer was sunk.

The Belleau Wood was a more comfortable ride than the destroyer had been, and my sleeping quarters were better. I found a former classmate from Pensacola, Morton Shapiro, on duty in the ship’s photo lab, surprising us both. The ship had a regular sick bay, and I could have the bandage on my leg changed there. (It still had not completely healed, but did seem to be a bit better.) My new battle station was on a searchlight platform on the top of the small island which was the ship’s command center. It was a strenuous climb to get up there each time the general quarters gong sounded, but it was a great vantage point and had the advantage of being able to look directly down to the level below where radar plot was located. Radar detected incoming aircraft long before they could be seen. Contact was usually confirmed at 100 to 80 miles out and I could watch the movement toward us as the radar men plotted the positions on a large plastic-covered board. A dot in the center marked our ship's position and concentric circles showed the distance to a row of marks that indicated an approaching kamikaze. By checking radar plot, I was ready long before they came within range of my cameras. I checked the cameras and removed lens caps when they reached the 15 mile ring on the plot.

The USS Belleau Wood, CVL

24, a light carrier of the Princeton Class.

Photographed from the McKee during the Iwo Jima operation.

The defense against suicide planes was good gunnery. First, the task force depended on patrolling fighter planes to shoot them down before they could get near the ships. When that failed, as it often did, the screening destroyers would open fire. If they penetrated inside the destroyers, heavy firepower of the cruisers and battleships was brought to bear, and finally, if they were able to get that close, the large carriers at the center of the task group fired too. The anti-aircraft guns were radar controlled on the large ships, but not on the Belleau Wood. She had only one 5-inch gun, stern-mounted, designed for anti-submarine work. It couldn’t fire at a high enough angle to be effective against airplanes. There were a number of quadruple 40mm guns, without radar control, and numerous 20mm, but combat air patrols and the other ships were really our main protection. The kamikaze pilots used a number of different tactics. One which worked successfully several times was to come in close behind a flight of our returning planes. Radar could not distinguish them from the rest of the flight and they would penetrate all outer defenses. One followed the Belleau Wood’s fighters right into the landing circle before he was noticed and shot down. With his engine knocked out, he crash landed in the sea less than 100 yards off the port side of the ship. The gunnery officer had sounded the claxon horn to signal cease fire as the plane hit the water. As his plane sank, the pilot climbed out on the wing, and the 20mm guns along the catwalks began firing, cutting down the pilot and hastening sinking of the wreckage. It was rumored that the gunnery officer spoke into his phone saying, “kill that s.o.b.” just as he sounded cease fire. Not a pretty sight. Seeing that and the red "meatball" insignia on the wing as it sank remains in my memory. I happened to be on the catwalk on the port side of the ship so had a good view. I didn't reach my usual battle station for there was almost no time between when GQ sounded and it was all over. Another kamikaze tactic was to fly just above the wave tops, to evade radar. Often they came in at high altitude, above 25,000 feet, beyond the range of our guns. From there they would choose a target and dive. Most of the planes were Zeros, but sometimes other types were used. Near the end of hostilities they also developed a very fast rocket powered plane. Flying at over 500 miles an hour with 2000 pounds of high explosive in the nose, it was too fast for our radar-controlled guns to track. It didn’t carry the extra weight of landing gear! Because the rocket engine could burn only a short time, these flying bombs were carried underneath a two-engined bomber and released when within rocket range, about 55miles. Fortunately for our side, the bombers were slow and usually destroyed by our fighters before they could get within range. We called them Baka Bombs, I am told Baka means foolish in Japanese. I don’t know if the pilot rode in the bomber until just before launch, or if he rode in that cramped cockpit from takeoff. Just after we landed in Japan I was at the base where pilots trained for their one-way trips. I saw and photographed some of the Baka Bombs. There was one that had landing gear, apparently for training?

A near miss at dawn on the USS

Hornet about 90 miles off Kyushu, southern Japan, March 19, 1945. This

was the same day as the Franklin disaster, where 724 men were killed and

265 wounded.

In the East China Sea, on the seventh of April, our aircraft sank the world’s largest battleship, the Yamato, (ancient name for Japan) sailing from Kyushu with a light cruiser and eight destroyers. All were sunk. Planes from the Belleau Wood were launched while too far from the target (about 250 miles.) for them to return with the fuel they carried. By running the ship at top speed toward the target while they were airborne, they could return just before running out of gas. About 300 aircraft attacked the Japanese ships, pounding with bombs and torpedoes until 14:23 when the big ship went down. Torpedoes were used against the port side only, to cause her to take on water on just one side until instability made her roll over. When that happened, and as she was sinking there was a tremendous explosion inside the ship sending smoke several thousand feet into the air. None of our surface ships were near enough to join the action. On the following day our battle group passed through a large oil slick left where the battle had taken place. I saw a few small pieces of floating debris, but nothing else. I recently read an account which says there were 269 survivors, but I didn’t hear of it then. We had been told the Yamato had 21 inch guns, five inches larger than our largest battleship’s guns. In accounts I have read since, the guns were said to be slightly more than 18 inches. Still bigger than our 16’s by over two inches. Those big guns had been designed for the old-style sea battle between battleships but had never been used that way. Without adequate air cover, this remnant of the once strong Japanese fleet was unable to reach Okinawa to carry out its plan to stop our invasion there. It wasn’t a completely one-sided fight, however. Anti-aircraft fire was fierce, and we lost many of our attacking planes. The Belleau Wood bomber squadron lost one of their ten torpedo bombers in that battle. This type of aircraft was the Grumman Avenger, (they were also built by Martin, designated TBM, instead of TBF. The designation stands for torpedo bomber, M for Martin or F for Grumman.) They could carry a heavy load, but were slow, and were therefore more vulnerable to gunfire. I doubt they could do more than 250 knots in a dive. There were no target seeking devices on torpedoes then, so it was necessary to fly close in and straight at the target to score a hit. Only three of the original ten torpedo bomber crews in the Belleau Wood’s squadron were left after Okinawa. One of the pilots lost in an earlier action was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, posthumously, while I was aboard.

End of Section 1. (See Section 2)