Section 2, War Stories by Lyle Hansen Copyright 2002

Ceremony on the flight deck of the

Medal of Honor; TBF at deck’s edge.

The

My leg acted up after a few weeks

on the

There was another patient who had a severe case of the fungus infection we called jungle rot. They had tried all the usual remedies, none of which helped, so had decided to try penicillin. The poor fellow had been wrapped with penicillin-soaked bandages over most of his body. Instead of helping, it seemed to react with the fungus and made the situation much worse. When I last saw him, he was in constant pain, and wrapped like a mummy from head to toe. He was transferred to a hospital ship later when we moved out of the combat zone. I was in sick bay for about a week, and very relieved when allowed to get out, especially because the doc didn’t have to do the amputation he threatened. Listening to the short wave radio in sick bay, we heard Tokyo Rose report that the Belleau Wood had been sunk by a kamikaze! There had been another near miss on the ship that day, but no damage, and we got a big kick out of hearing it. Her broadcasts were usually so far off the mark I felt she did more good than harm to our morale. When she was tried and sent to prison after the war, I thought some of the fuss made over it was overdone. Since she was a U.S. citizen, as a matter of law, I suppose she was a traitor.

The closest call I had was another

kamikaze that nearly blew up our ship. We had been called to general quarters

for the umpteenth time, and I was at my station on the high searchlight

platform. Radar plot showed one bogie

(enemy airplane) well outside the destroyer screen to our starboard. Before he was visible to me, the destroyers

began firing, and the black puffs of smoke from five-inch anti-aircraft shells

marked his location. He then went into a dive and passed between a pair of

destroyers, low to the water. He headed for a cruiser that was between our ship

and the destroyers, about half a mile away.

Now quite visible, I was sure he had targeted the cruiser, and got ready

to get pictures of what looked like a sure hit. There was a lot of firing, but

he seemed to have a charmed life. Suddenly he climbed up, passing over the

cruiser by what looked like only a few feet. As he dove back to near wave-top

level, it became clear that the Belleau Wood was his target, and his aim point

was the island under my station. At the

last moment I stopped trying to get that picture of the expression on his face

and ducked down behind a searchlight. I

fully expected to be blown sky-high.

Crouched behind the searchlight I waited for the explosion I was sure

would come. The guns were firing, there was a low-pitched thudding boom, but

not quite the explosion I expected. The ship was still moving at high speed. I

looked out to starboard and saw a huge plume of smoke and debris rising above

the flight deck up to the level of my platform, but rapidly passing astern. I

tried to stand up, but found my legs wouldn’t support me. It was as though they were made of

jello. I was shaking uncontrollably. After what seemed a long time, but was

probably only a few seconds, I was able to rise and see what had happened. Obviously we weren’t hit. The quad 40mm guns just below my battle

station were credited with stopping that kamikaze just a few feet from his

intended target. One piece of debris that came aboard was a piece of shrapnel

about a foot long and perhaps four inches wide.

It was imbedded in the flight deck, and was brought to the photo lab to

be photographed and included in the action report. From its thickness and the machining marks on

its circumference, it appeared to have been from an armor-piercing artillery

shell rather than a conventional bomb. Had our light armor been pierced, and the stores

of aviation gasoline ignited, much more than just the ship’s command and

control center would have blown sky-high.

One crewman, apparently believing the ship to be hit, jumped overboard.

Search planes were sent out to look for him, but he wasn’t found. Reading through various accounts of the

Kamikaze attacks on the task force, I found that this happened April 6. It was a part of the first of several mass

attacks called kikusui by the Japanese, meaning floating chrysanthemum. 355 kamikazes attacked during April 6 and

7.

President Roosevelt died in early

April and the ship’s chaplain held memorial services on the flight deck. There was quite a sense of loss felt by

everyone.

Sometimes things would happen to

put a bit of humor into the grim aspects of being in a war. With constant calls to general quarters, the

lack of sleep tends to condition a person to sleep whenever an opportunity

arises. In one rare lull in the action,

a complete white-glove type inspection of the ship was ordered. The photo lab crew had cleaned and polished

for hours getting ready for it. The

first class petty officer in charge, waiting for the inspecting officers to

arrive, sat down to relax when all was prepared. He dozed off, and was sound asleep when the

officers arrived. Taking in the

situation, the skipper reached for the intercom, and quietly called to report a

fire in the photo lab. Alarms went off, and “FIRE, FIRE, FIRE IN THE PHOTO

LAB!” sounded loud and clear over the ships announcing system. The embarrassed

1st class awoke with a start.

He was not amused, but everyone else was.

Fresh water was rationed, so there

were “water hours” when fresh water showers could be taken. After a short

period of about 45 minutes, the fresh water was shut off and only seawater was

available. If you have ever had a saltwater

shower, you know that ordinary soap doesn’t work and while you may feel clean

while you’re wet, you’ll feel sticky when you dry off. My friend Morton Shapiro was in the shower,

nearly finished lathering up, when the water went off completely. Not even seawater was available for a rinse

that time. Not at all happy, he returned to the photo lab with his towel and

soap. He locked himself inside a darkroom and filled a large stainless sink

with warm fresh water and had a nice tub bath!

Preflight

briefing in the ready room.

I photographed the pilots and flight crews,

usually just before a mission. When they returned, exhausted and grateful to be

back on the ship, they didn’t want me to point my camera at them. Flying from a carrier is dangerous even when

not under combat conditions. Accidents

happened all too frequently. An engine failure during launch ruined the whole

day! The forced landing in the sea was generally survivable, but only if the

pilot was able to maneuver out of the ship’s way. The angled flight deck used

on today’s super carriers didn’t exist.

A photographer in one of the other

units, full of bravado, was eager to go along on a mission. Considerably older than most of us, he even

had a son in the navy. Assigned to one

of the other carriers, he finally got his chance to ride as the fourth man on a

TBF flight over Okinawa. The engine lost

power just off the catapult and they went in the drink. While the ball turret gunner and the pilot

can escape quickly, the radioman and anyone else in the bilge cannot. The photographer was the last man out, and by

then the heavily loaded plane was already below the surface. When I talked with him at Guam, he said the

airplane was ten or twelve feet under when he finally got out, and he didn’t

think he was going to make it. He kept

telling me how kindly the doctor on the destroyer that picked them up had

treated him. His belligerence had disappeared, and he was applying for shore

duty.

Fighter pilot ready to board his

Hellcat. He has his parachute harness,

inflatable life vest, clipboard,

oxygen mask,

and 38 caliber pistol in a shoulder holster.

Plane

handling crew preparing a hellcat fighter for launch.

Fighter pilot ready for takeoff.

TBF Radioman at

his station in the plane’s “bilge”. 3rd

man in the flight crew, he was also the tail gunner.

One of our TBF’s was hit while over Okinawa. A 20mm

explosive round exploded inside the radio operator’s body, killing him

instantly and splattering his body all over inside the airplane. There was no

major structural damage to the plane. Scrubbed out, and with a patch on its

skin, the airplane was soon ready for flight.

However, the odor in the radioman’s station was sickening, and the

replacement crewman became ill while in flight.

The airplane was scrubbed again, and wiped down with oil of

wintergreen. Still the crew became sick.

The airplane was finally jettisoned into the ocean after removing vital spare

parts. There was no room to store a

plane that couldn’t be used.

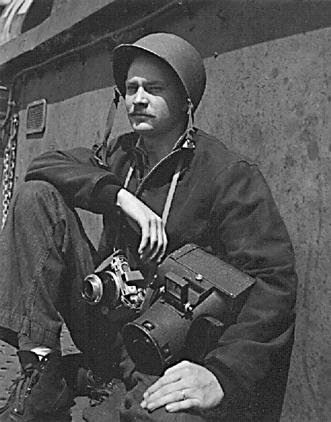

Watching for planes to return from Okinawa on the

Belleau Wood’s catwalk at the edge of the flight deck. My friend Morton Shapiro made this photo

of me.

At times we could listen to talk

from aircraft while they were in flight.

In support of troops on the ground, the planes would be sent up but held

orbiting around some point until directed to a target by the troops below. On

one occasion, when the orbiting had gone on for some time and reserve fuel was

running low, a pilot began grousing over the radio. “This war is all screwed up. The people running it are all screwed

up. Even I am all screwed up!” A belligerent voice cut in with “This is Bull

Durham, identify yourself!” The pilot came back at once saying, “I’m not that

screwed up!” (Bull Durham was the code

name for Admiral Halsey, commander of task force 38.)

Landing signal officer guiding a

plane in for a landing on the Belleau Wood.

Safely down, the Hellcat’s

tailhook is retracted as it taxis forward.

Plane handling crew parking a Hellcat on the forward

flight deck. Ready to be refueled

and rearmed for the next flight. The damaged fighter in the lower

picture was flown by one of the pilots I photographed just before he took

off. Nearly out of fuel, with the

engine missing and leaking oil, he made a hard landing and both tires blew

out. He had been very concerned

about the big hole in the left wing. After climbing down from the cockpit

he nearly fainted when he saw the left elevator had almost been shot off of

the tail.

Aviation

ordinancemen arming fighter with five-inch rockets

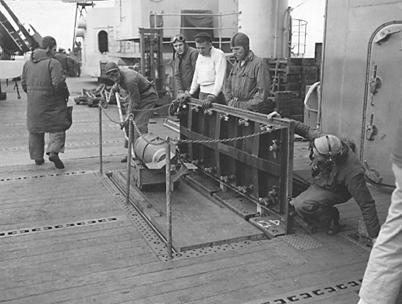

Anti-personnel

cluster bombs being prepared underneath a TBF bomb bay.

Above: 500 lb.

bombs wait on the flight deck to be loaded. Left: 500 lb.

bombs falling toward their target on Okinawa from TBF. Photo taken by the radioman through the

open bomb bay doors, He borrowed the camera. My officer didn’t want me to fly on

combat missions, I don’t know whether it was because I was married and had

a young son at home, or if he thought my sore leg might be a problem. If I had gone, I would have been the

fourth man in a three-man airplane. Not being trained as an aerial gunner,

I couldn’t be a regular crewman, and would have ridden in the bilge with

the radioman.

One afternoon there was a real

emergency in the torpedo room. A chief

petty officer working there went berserk.

He was standing beside a partly-assembled live warhead with a ball-peen

hammer threatening to blow up the ship if anyone came near him. There is a full ton of high explosive in the

warhead of a torpedo. It was said he had been drinking “torpedo juice”, the

denatured alcohol used as fuel in the torpedoes. Certainly something had

affected his mind. It was very serious situation, in the end handled very well

by some of the marines on board. A couple of them distracted him with

conversation while another came up behind to deliver a knockout blow and grab

his hammer. I never heard what became of

the chief, but I suspect he was kept under lock and key for quite a while.

500-pound bomb

being brought up to the hangar deck by elevator.

Cigar-smoking ordinance man loads a 500 lb bomb into the

bomb bay of a TBF on the flight deck.

Filling a Hellcat fighter’s wing tank with fuel for

extra range. In some cases these had Napalm added for dropping on

enemy positions. The sequence at left shows a hellcat landing before the

plane ahead had taxied forward and the barriers raised ahead of the landing

space. He said he was waved aboard but the LSO said he waved him off. Even so, all would have been fine except

his tail hook broke! He crashed into

his wingman in the plane ahead killing the first pilot instantly. The fire that started was so hot that

both planes were pushed into the sea in order to save the ship. The second pilot was rescued by the man

in the asbestos suit, but the body of the other one was still in the

wreckage when it had to be jettisoned overboard.

Kamikaze attacks had been going on for about a

month, and supplies were running low.

The food seemed to be down to a sort of subsistence level, the main diet

being canned tomatoes, rice and Spam.

Beans for breakfast was an old navy tradition, and sometimes there were

scrambled eggs. The eggs, were powdered, and when reconstituted were of a

rubbery texture with a greenish color.

The taste was hardly like eggs.

So, when our group pulled back from the combat zone to meet a convoy of

supply ships, we felt things would improve.

Tankers refueled the ships with fuel oil and aviation gasoline. All day

there was a steady stream of slings filled with rockets and bombs hoisted to

the flight deck and then stowed below.

Finally, late in the afternoon, packing cases of food were brought on

board. They contained more canned

tomatoes, beans, rice, Spam and dehydrated eggs.

Supply ship

alongside transferring cargo.

Cargo net coming aboard with more bombs.

Storing the supplies.

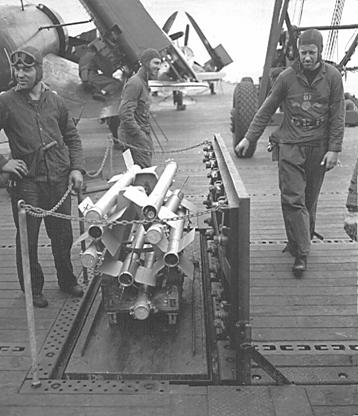

Rocket motors on the elevator coming up to be

assembled by ordinance men prior to installation on the Corsair fighters on

the flight deck.

5-inch warheads for rockets

Attaching 5-inch war-heads to rocket motors on the

flight deck; Man on the right is over the housing for an arresting

cable. These cables are caught by

the aircraft’s tailhook when landing on the flight deck.

Dud rocket to be

dumped over the side. Defective rockets brought back to the ship would detach

from their mounts and go slithering down the flight deck when the arresting

cable stopped landing planes. I saw recent pictures on the internet showing the

same problem existed with planes returning to the USS Stennis from Afghanistan

Clearing the flight deck for an

emergency landing.

SB2C returning to the task force from Okinawa. Photo taken by a Belleau Wood aircrewman.

The second fatality of a combat photographer during the time I was one of them occurred on a flight in a plane like the one in the picture above. Badly damaged by

anti-aircraft fire, and with the intercom knocked out, the photographer in the rear seat apparently thought they were about to crash as the plane continued to lose altitude. He bailed out, but was not rescued. Ironically, the pilot was able to get back and made a safe landing.

Many ships in the task force were damaged by the Kamikazes, but few, mostly destroyers on picket duty away from the main force, were sunk. If the damage was slight and repairs could be made while underway, the ship stayed to continue the battle. One hit on the Hornet resulted in major damage to one of her elevators. When the action was over and the damage assessed, an announcement was made that the Hornet would leave our battle group with two destroyers as escorts and go to Bremerton, Washington for repairs. While watching her make a wide turn and head eastward, for a few moments I wished the Belleau Wood could have a similar bit of damage! Home never sounded so good. Being aboard on temporary duty, I’m sure if the ship had left the battle zone, I would have been moved to a different ship anyway. Fortunately, the Belleau Wood had only near misses while I was aboard. Our gunners and the ones on the ships around us were either very good, or as I came to believe, it was probably just good luck. If you happen to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, you may be killed. But there are times as well, when one can definitely be in exactly the wrong place and still be completely unscathed. Logic doesn’t seem applicable to everything.

After nearly two months of almost

continuous action, our battle group withdrew.

Okinawa, while not completely secure, was entering a mop-up phase. The

army and marines had to continue in those efforts until mid-June as I recall. During the night before we reached our Ulithi

anchorage, the destroyer squadron held maneuvers, making practice torpedo runs

on our own battleships. Running in a

tight formation at full speed in darkness, signals somehow became confused. The

squadron made a turn in one direction, as ordered, but one ship turned in the

opposite direction. The result was a collision between the Ringold and the

Yarnell, one shearing the bow off the other.

Fortunately, since both ships were at general quarters for the torpedo

drill, there were few injuries, but I think I heard one man was killed. Chief’s quarters on a destroyer are at the

extreme end of the bow. They were sheared off on one ship and smashed flat on

the other. Watertight bulkhead doors are always closed while at general quarters,

so there was no danger of sinking. The

tin can without its chief’s quarters was towed into Ulithi stern first the

following day.

It was finally time for me to

leave the Belleau Wood and rejoin CPU#6.

I had only a few minutes notice, and a new regulation I was unaware of,

stipulated that anyone leaving the ship must have a white hat. No blue-dyed ones, no baseball caps, must be

a white hat. I didn’t have one. Ship’s Service wasn’t open, so I couldn’t buy

a new one. Frantically searching for a

solution, I came across my friend Morton Shapiro, and he was wearing a white

hat! There was no time left for formality.

I lifted the hat from his head, bid a hasty goodbye, and was down the

gangplank to the waiting boat while Mort was still yelling. I didn’t see him

again while we were both in the service, but tried to make amends years

later. While in Chicago on a trip for my

employer, the Boeing Co., I remembered Mort’s home town was Chicago. I found his name in the phone book, called

and bought him a good lunch while we reminisced about our times together.

The Bennington and the San Jacinto returning to the

Fleet Anchorage at Ulithi Atoll.

(See Section 3 to continue.)