Section 3, War Stories by Lyle Hansen. Copyright 2002

After the members of CPU #6 were together again on the Bennington, we learned that we would be flying to Admiral Nimitz’ new headquarters at Guam for a rest period. The airstrip was on the largest of the islands ringing the lagoon, Falalop. Metal mats had been laid over the leveled sand and coral to form a short runway ending right at the water’s edge. The nine enlisted men and one LT JG along with our equipment and personal gear took up most of the space on a two-engined transport. Included in our orders was an air transportation priority two. This was a very high priority, since most of the admiral’s staff officers only had priority three. Using it, we inadvertently bumped a number of CINCPAC officers who wanted to catch that flight. After that, our priority was changed to a three, and rank could exert privilege with the priorities equal!

Our 400-mile flight to Guam was uneventful, and the time was passed in a bridge game. One of the few times I ever enjoyed that game, as no one was so expert as to make my mistakes unpleasant. We were transported by truck to the new CINCPAC headquarters after landing. It was at the highest point on the island, an elevation of 1100 feet. Here we settled into a newly erected Quonset hut with mosquito nets over folding cots.

The road up to

CINCPAC headquarters from the town of Agana, Guam.

Getting into the chow line for the first time at the mess hall, there was a startling reminder that this ground had only recently been converted from a battlefield. An unbleached human thigh bone lay beside the path where we stood in line. My appetite wasn’t improved by that grim discovery! The food was an improvement, however. It was still standard navy fare, but there was more variety.

There were several of the combat photo units at CINCPAC and we would have muster each morning with a roll call in front of the very large Quonset hut used as our headquarters. There were several of these warehouse-like huge huts higher on the hill, the uppermost one containing Admiral Nimitz’ offices. The ones between held offices for his staff members. After the muster, there was usually some lecture or demonstration concerning our work, viewing of recent film footage, and always critiques, generally constructive. (My wife still doesn’t like to go to movies with me because I find fault with the camera techniques!) Most of the time our afternoons were free, but sometimes we had photo assignments to do somewhere on the island.

Home is on the right, to the left,

the head, with no limit on hot water in the showers!

Our Quonset hut was at the edge of the jungle, and papaya, coconut, pandanus, and even breadfruit grew there. Fascinated with this, I and a friend followed a trail leading into the jungle. Within a few hundred feet we were looking at the remains of Japanese soldiers, some in groups and some solitary. Mostly all that remained were bones, scraps of clothing, the peculiar shoes having a pocket for the large toe, sometimes hobnailed boots and helmets. We took a few pictures but didn’t stay long. Then, a day or two later, I thought it would be interesting to explore a little further on my own. I followed the same trail deeper into the thicker growth and downhill. Since I was taking a hike, I didn’t bring a camera to weigh me down. I soon found myself in jungle with a canopy of growth overhead cutting out the bright sunlight. Going further, I came to a rock ledge where the trail faded away. Looking to find where it continued, I parted some undergrowth to see over the ledge and found that the jagged rock dropped straight down for about eight feet to the trail below. In the dim light I saw a Japanese soldier crawling up that trail. I felt the hair on the back of my neck stand erect. Then I realized he was dead and obviously had been for probably months. In that dim light, and with his helmet over what remained of his head as well as his uniform still being intact he gave me quite a start. He had been pulling a roll of telephone wire behind him as he was moving up the trail when he met his end. I decided that was enough exploration and went back where I belonged. That same afternoon there was a sound truck on the road just below us shouting into the jungle in Japanese. Then I learned there were many of them still hiding all over the island. The sound truck was trying to get them to come out and surrender. I didn’t try any more solo exploring!

Japanese remains at the

edge of the jungle. May, 1945. Photo by

Emil Petryk.

Broken Japanese helmet and skeletal remains

just outside the clearing made for CINCPAC headquarters.

On V-E day at Guam, there was no great hullabaloo celebrating the end of the war in Europe. It seemed far from over in the Pacific, and while there was progress, no one felt that it could end quickly. At an intelligence briefing we learned the next major operation planned was an invasion of Japan’s most southern island of Kyushu. Casualties were expected to be very high, even after further strikes against all of Japan and their military in China. At this same briefing we were issued “blood chits” and a hand signal mirror for use if shot down in enemy territory. One of the briefing officers made a very interesting and detailed presentation on use of the blood chit to get out of China. He seemed to have made the trip himself, but being from the OSS, (the Office of Strategic Services was the agency which later became the CIA) he didn’t say for sure. The chit was really a small waterproof US flag containing a promise from the US government to pay 10,000 dollars to the person or person who would help the bearer return home. This was printed in all major Asian languages. He gave the impression that the main difficulty in getting out after being downed over China would be that you would be moved slowly through the country from village to village while each local community wined and dined you celebrating its good fortune in sharing the $10,000.

My unit helped make a training film titled “a Cure for Kamikazes” at a gunnery training station at the south end of the island shortly after arriving. Shipboard gunners were sent there for training, firing at drones and towed targets. A rocky cliff stood just behind this facility with a high perimeter fence between. There were searchlights and guard platforms to protect against Japanese still in the jungle above. Apparently the frequency of attacks had slowed, for when asked about it, I was told: “Yeah, they’re out there. We see them sometimes up on the rocks, but if they don’t bother us, we don’t bother them!”

Having seen a really nice sandy beach nearby when we drove out there, I and a friend decided to have a swim, since we had finished our work and we would be waiting for the others for another hour or so. This was the only beach I saw at Guam where you were not likely to cut your feet on coral. We hung our clothes on the bushes and went in. The water temperature was perfect. After a while we were joined by a slightly pot bellied older man wearing standard navy issue trunks. We thought he was probably an old chief, and he enjoyed playing water games with us. He rolled over on his back, spouting water in imitation of a whale. Finally tiring, we told our new friend goodbye explaining that we had to get back to our group. When we dressed and went back up to the road, we realized why the man’s face seemed familiar. At the edge of the road was a spanking clean jeep painted with five stars and a marine in a stiffly starched uniform. We hadn’t recognized Admiral Nimitz! I’m sure he knew it and got a little fun out of being just a regular sailor for a while.

We often saw the admiral in the morning walking past our headquarters building on the way to his office while we were waiting for muster. When members of his staff were with him, we had to stand at attention and salute, but at times if he was alone, he just looked over with a smile and said, “Morning, boys.” How could you not like an admiral who would do that?

My ex-Pensacola instructor and room mate at the Honolulu Y came back from an assignment with the marines on Okinawa. He had been using a new Cineflex 35mm motion picture camera and was anxious to view his footage. When the print was screened, nearly all was unusable, due to a light leak between the magazine and the camera body. Poor Chief Erickson was so frustrated and angry, he wanted to put the Cineflex on a block and smash it with an axe. If there had been an axe available, I’m sure he would have, and who could blame him? He had some fine footage, but with the film streaked with fog from light leaks, it was ruined.

CINCPAC photographers at home on Guam.

Combat

Photographer and pre-war Disney Studio sound technician E.R. “Ted” Baker.

The bearded man in the bottom photo was another of my Pensacola classmates. One day as he sat under a coconut tree writing a letter, someone asked him, “Who are you writing to, Bake?” He answered, “Walt, I have to answer his last letter.” He kept up a regular correspondence with Walt Disney, telling him what he could of his activities. Later a reply would come, telling of the activities at the Disney Studio, and signed, “Walt”. Baker had worked on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs as well as other prewar Disney productions before he went into the Navy. He was one of the many Hollywood film industry technicians who helped the navy produce training and public relation films at Anacostia, D.C. He had asked for a more active role and was sent to the school at Pensacola where I first met him. After the war and back in Hollywood, he did the sound work on Mr. Magoo, and others. He was a Bellingham, Washington native.

Ruins of church in Agana destroyed by one 16-inch shell during invasion by the US.

Agana, the main town on Guam, had been largely destroyed when the US retook it from the Japanese. Battleships with the invasion force bombarded it with 16-inch shells. I was struck with the accuracy of one hit on a large church. I thought at first it was a senseless act of sacrilege, but found that the enemy had been using it, thinking, I suppose, that they might be safe there. A single shell came in through the reinforced concrete gable at the front and exploded inside, blowing most of the rest of the structure away. I saw the butt end of the 16-inch projectile lying inside in the rubble. There were also some remnants of Japanese supplies, a box of rather old dried fish, some rifle ammunition, and a few empty sake bottles.

Sunken sip in Talafofo Bay, on the eastern side of Guam.

Evidence of the fierce fighting to retake this 40-mile long island was everywhere. A picturesque little village at the head of tiny Talafofo Bay had Japanese foxholes dug into the graves at the village churchyard. At the mouth of the bay lay a sunken ship, its masts and funnel above the water. Shattered field guns, blasted shore battery emplacements, and caves still containing live Japanese ammunition were common.

Foxhole in the graveyard. Chamoro village at the

head of Talafofo Bay.

Ammo and

hob-nailed boot at the mouth of a cave.

Lyle Hansen examining

remnants of a field gun. Photo by George

Edinger.

Getting a close look

at a Japanese shore battery gun emplacement.

Photo by George Edinger.

While I was active in

getting to see as much as I could of the island, I also got a lot of rest. On many of the free afternoons, especially

just after we arrived, I took a lot of naps.

Perhaps the tropical heat, but I think too, I was still wrung out from

the long day and night hours at GQ on the Belleau Wood. Others had the same

need for more rest than usual. One day I played a trick on one of the men who

took more naps than anyone else in our unit. He would crawl under his mosquito

net shortly after noon chow and often still be there when the evening mealtime

came. We all wore marine corps combat boots, “Boondockers”, and in that climate

cut holes in them for ventilation to help stop the spread of jungle rot. (I

think everyone had some of this fungus, an aggressive relative of athlete’s

foot.) This habitual sleeper had a habit

of swinging his legs over the side of his cot and putting his feet into his

cut-out boots before he stood up. On

this occasion, in his drowsy condition, he didn’t notice that his boondockers

had been nailed down to the plywood deck.

It really did look comical when he tried to walk away! Some days we played volleyball, but I was

never very enthusiastic about it. The

sun was so hot that a little exertion seemed more than enough.

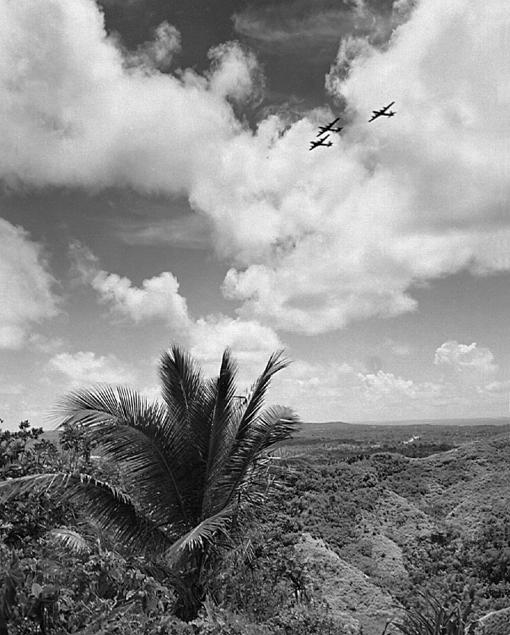

A flight of B-29’s returning to

base after bombing Japan

It was personally

gratifying to me to see the B-29’s on Guam. I had worked at the Boeing Company for the first two

years of the war making photo templates of engineering drawings to get it into

production, and now to see it doing the job it was designed for, gave me a

thrill. Its existence wasn’t even known

to the general public until the summer of 1944.

When the experimental first airplane crashed during a test flight in

1943, the Seattle newspapers said that a B-17 had crashed. Not only was the airplane experimental, but

its engines, too. When an engine fire

developed while on the east side of the Cascade mountains, the Boeing flight

test crew did everything possible to bring it back to Boeing field in

Seattle. Had they bailed out and let it

crash over the mountains, their lives would have been saved. As it was, all perished when it crashed into

the Frye packing plant beside the field.

I was working third shift in the photo template department then, and on

my way to work I knew from the headlines in the newspaper that it wasn’t a B-17

crash, not with an 11-man crew! Engines

continued to be the big plane’s main problem even while it was operating from

Guam, Siapan and Tinian.

USArmy Air Corps 20th Air Force B-29 at Guam.

By the summer of 1945,

the Army Air Corps people we talked with were optimistic about the war ending

soon. There was less resistance to the B-29 raids now, since Iwo Jima had been

taken. Japan was taking a pasting. Those of us who had experienced Kamikazes

weren’t convinced it would be over quickly, especially knowing we were soon to

go back into combat.

There was another

incident at CINCPAC while we were there that may illustrate how close the

remaining Japanese on the island were. (About 9000 were still in the jungle

when the island was declared secure.)

Marine sentries guarded Admiral Nimitz’ living quarters. One night while standing his watch, the

sentry had a call of nature and went to the head. He set his carbine down at the entrance for

just a moment. He should have known better, as when he came to pick it up, it

was running away in the hands of a Japanese soldier! I wouldn’t care to have been in that man’s

boots. He was lucky he wasn’t shot by

the Japanese with his own piece. I think

we were all a bit more careful where we kept those Colt 45’s we had been

issued. I know I cleaned and oiled mine,

and made sure a few clips of ammunition were kept handy.

At the beginning of our next operation we went to the

Philippines, flying to the island of Samar, where we lived in tents at the town

of Guiuan while waiting for the fleet to assemble in Leyte Gulf. The tents were set up in the churchyard of a

large very old church, and we actually had gravestones under our cots in the

tents. Some of the dates on the stones

went back into the 16th century. The altar piece inside the church

was hung with silver bars, and we were told these had just been brought back to

the church from their hiding place in the jungle where they had been kept

during the Japanese occupation. There

were still mop-up operations going on, and Filipino guerillas were hunting

Japanese who had retreated into the jungle. The government had placed a bounty

on them and to collect this the guerilla soldiers brought severed heads to the

town plaza as proof of their efforts. I was told that the pile of heads had

grown so large and smelled so bad that they moved the operation out to the edge

of town.

At the beginning of our next operation we went to the

Philippines, flying to the island of Samar, where we lived in tents at the town

of Guiuan while waiting for the fleet to assemble in Leyte Gulf. The tents were set up in the churchyard of a

large very old church, and we actually had gravestones under our cots in the

tents. Some of the dates on the stones

went back into the 16th century. The altar piece inside the church

was hung with silver bars, and we were told these had just been brought back to

the church from their hiding place in the jungle where they had been kept

during the Japanese occupation. There

were still mop-up operations going on, and Filipino guerillas were hunting

Japanese who had retreated into the jungle. The government had placed a bounty

on them and to collect this the guerilla soldiers brought severed heads to the

town plaza as proof of their efforts. I was told that the pile of heads had

grown so large and smelled so bad that they moved the operation out to the edge

of town.

Church at Guiuan, Samar.

Carved

doors at entry. Church

interior in lower photo.

Filipino soldier.

Outrigger canoe on Samar’s Letye Gulf shoreline.

While waiting for the

fleet to arrive, Jack Cathey and I decided to make some photos of the local

people as they went about their everyday activities in Guiuan. However, each time they saw a camera pointed

in their direction, they wanted to strike a pose. So we carried our cameras in a dangling

position with a cable release ready to trip the shutter while walking around

looking in a different direction than the camera. Some of the results didn’t

frame the subjects very well, but we did get the natural expressions we wanted.

Buying bakery goods.

From my short stay on Samar, I had the distinct impression that the people there had a definite mistrust of us. They wanted our money, and that was about all. I didn’t feel safe and didn’t wander around by myself. I was also surprised by the amount of gambling I saw. It appeared that everyone was doing some sort of gambling game, from small children on up. I saw two young boys playing heads or tails for paper money. Without a coin, they were flipping a clam shell! Some others playing cards were so young their tiny hands could hardly hold the cards. One afternoon several of us went to see a cockfight, The only one I ever saw. The participants brought their fighters in bamboo basket cages, walking with jaunty strides to the ring. To see the same man carrying his dead rooster home, dejected and likely broke or in debt, is something I wish I had photographed, and now I have no idea why I didn’t.

A two-Bolo knife man.

Street gamblers.

This lady was making cigars and selling them on the

street. Her supply of tobacco is on the chair beside her,

and she was hand-rolling them using her own saliva as a binder. A Navy pilot friend of mine who had also been in

Guiuan at about that time told me he had bought and smoked some of

them. He had not seen her make them

and was appalled by my description of the process.

Outrigger under sail, there

are chickens up forward.

Young spear fisherman.

Units of the fleet began to gather, anchoring in Leyte Gulf. As soon as space on board became available we moved out of the tents in the churchyard and crossed over to Tacloban on the island of Leyte, in an LST. We went ashore on the same beach where MacArthur had his picture taken wading ashore. The picture was published in the states with captions which led the people at home to think the general went ashore under fire with his troops. He actually came three days later, and even the landings on the first day were not heavily contested. The fighting came afterward, away from the landing sites. I believe Life Magazine photographer Carl Mydans staged MacArthur's photo. There was no need to wade ashore. Landing craft were able to put people ashore there without getting wet.

Combat Photo Unit

#6 arriving at Leyte with their equipment and personal gear. Left to right:

Helton, Brunton, Higgins, Guttosch, Hayes, Cathey, Hansen, and Davis. Branson took the photo and Mr. Rogers hadn’t

arrrived yet.

The man peeking

around Don Helton’s shoulder was just a curious bystander.

From Tacloban we went to one of the Essex class

carriers now anchored in Leyte Gulf. I

can’t recall which one, but it was very crowded, almost no empty berths. I was assigned a rack down in the boiler room

area. The ship being at anchor, there

was very little air circulation, and with the heat from the boilers, it was

very uncomfortable. When I got up in the

morning I found my perspiration had soaked all the way through the

mattress. After that I slept on the

catwalk on a steel deck. The waffleboard

non-skid pattern was imprinted in my back, but it was preferable to being in

the boiler room. I developed a sore

throat and a nasty cough while on that ship. Going on sick call, I hoped to get

some aspirin, but they put me to bed in sick bay! I was told I had Cat Fever. I never did find out what Cat Fever was, but

after two or three days I was released.

One afternoon we watched

a pair of Army Air Corps P-38’s playing tag around the ships. They would fly

towards a ship, their propellers barely above the tops of the waves, and at the

last moment go into a steep climbing turn just over the vessel. I guess they were trying to show the navy

fliers how well a P-38 could fly. However, when they did this over the

Randolph, one of them misjudged a bit.

He sideslipped onto the flight deck, crashing into the parked planes,

and with the inertia of all that speed, slid off into the water. The P-38 pilot

was killed along with 13 sailors. Six or seven navy planes were destroyed by

the crash and fire. There was a light

rain falling at the time, or there would have been more men killed. Most of the men on the flight deck had gone

below to get out of the rain.

The Randolph had been hit by

kamikazes twice before, but this was the only one who flew a P-38!

The Randolph’s captain put in a call to the

commanding officer at the Tacloban airstrip, reporting what had happened and

asked if they would please keep their aircraft away from the fleet. The Air Corps commander said surely there

must be some mistake, his P-38’s couldn’t have done that. It must have been a Jap kamikaze. The Randolph’s captain said it looked exactly

like a P-38 to him, but as it had gone on over the side, he would have a diver

go down to take a look.

End of Section 3.

See Section 4 to continue.