War Stories, by Lyle Hansen

Section 4

Copyright

2002

The diving platform had been rigged and the diver was getting his hardhat bolted down when a call from Tacloban airstrip came through. Apologetic, the Army Air Corps CO said he was extremely sorry, and yes, there was a P-38 missing.

About three days later, CPU #6 moved to the Randolph. The yeoman who was to process our incoming records was busy with the records of the men who had died from the P-38 crash when we brought ours to the exec’s office.

Having been hit twice by Kamikaze planes, once when at anchor in Ulithi, and once off Okinawa, and now by the P-38, everyone on board the ship was very conscious of fire danger. Special steel shields had been welded around each watertight hatch opening in the hangar deck as a precaution against burning gasoline running into compartments below. Real effective shin barkers!

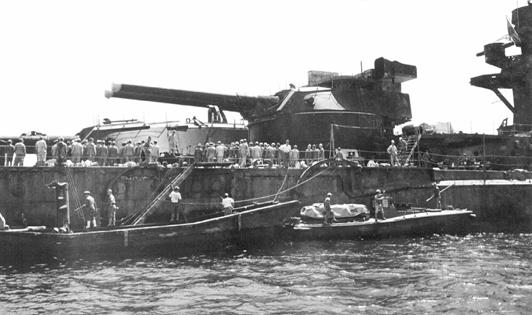

BB 60, the Alabama. Photo

lab at the Naval Air Transport Hdqts at Oakland NAS had this picture on file

when I had duty there after the war ended. I think it was taken before the ship

went into action while some dignitary was visiting. Camouflage paint was not yet applied.

When the task force was finally asembled at Leyte Gulf, in late June, I was assigned to the Alabama. And this time Jack Cathey would be my partner. On the assignments before I had always worked alone. We were told to document activities on a battleship in a similar manner to the way “Fighting Lady” had shown life on carriers.

The battleships held firing practice on the first night out when we put to sea. The power of those 16-inch guns was awesome. We couldn’t see much in the darkness, but when a gun fired, the blinding muzzle flash illuminated everything like a giant flashbulb. The concussion jolted the ship, and this was from just one of the nine guns! Maximum range was about 21 miles, and the projectiles were about the same weight as a small automobile. With radar fire control, they had an accuracy that had been impossible in the past. Since air power had become dominant, the main function of the large fast battleships was to protect the carrier task force. For this purpose, numerous five-inch antiaircraft guns had been installed. I think there were twenty of those on the Alabama. Equipped with radar fire control and using proximity fuses on the shells they fired, they presented a very severe hazard to attacking aircraft.

The Alabama’s five-inch guns watching

over the task force.

Before leaving Guam, our officer held a meeting about morale. Cathey told Mr. Rogers that it was getting more and more difficult to go out each time he went. I think we all felt that way, the war just seemed to go on and on, and what we had seen so far convinced us that the struggle would continue to be long and hard. For my part, while I agreed with Cathey, I said I felt like I wasn’t really getting anywhere in the navy, and that a promotion might help. Not long after, nearly everyone was raised one rating higher. I became a Photographer’s Mate, second class, having been third class since Pensacola.

The Alabama had one photographer in the ship’s company, a man by the name of Reagan, I don’t recall his first name. We were assigned to the N division, (N meaning navigation), as the navigation officer was also the photographic officer. There was a small darkroom on board and Reagan made us welcome. It was located in a space aft, between the inner and outer hulls, and if anyone had remained there at general quarters, he would have been locked in with no possible means of escape. Being nearly over the propellers, the vibration made it almost impossible to use the enlarger, everything shook out of focus, even though the top of the enlarger had been welded to the bulkhead, in an effort to synch the vibration.

Cathey, Reagan and Hansen by one of the five-inch gun

mounts. Reagan, the

Alabama's photographer, had hurt his hand when a hatch

cover slammed shut on it.

There were about 3000 men in the crew, so like the large carriers, the ship was almost a small city by itself. There was a brig in the enlisted man’s mess, located so that you had to pass it when in the chow line. The prisoners were guarded by marines who brought bread and water to those whose sentences required such rations. Watching this made you think you had better watch your step, which I’m sure was the whole idea. The captain had been commander of the cruiser Marblehead in 1942. It was badly damaged by Japanese aircraft off Borneo while operating with the cruiser Houston and six US destroyers under command of the Royal Netherlands navy. The rumor was that, wounded then, he now had battle fatigue and lived in constant fear. He stayed inside the 18 inches of armor around the conning tower while the executive officer seemed to run the ship. The men had nicknamed him “Old Marblehead.” They revered their original captain and told stories of that worthy taking the wheel himself to bring the huge ship alongside a dock, “just like a destroyer". I wish I could have seen that.

The task force moved up near the Japanese home islands and about ten days after leaving the Philippines the carriers launched a thousand-plane strike in and around the Tokyo area. There was almost no resistance from Japanese fighter planes. We didn’t know the reason at the time, but they had decided they would save their planes for mass suicide attacks against our invading forces when they came to the main islands.

About that time, we received Admiral Byrd on board. His expeditions to Antarctica and his flight over the North Pole had made him very famous. While he held the rank of rear admiral, the job he was given by the navy brass was that of bombardment observer. That task probably was usually performed by a Lieutenant JG. I suspected that since he attained his high rank by an act of Congress instead of normal channels, the powers in charge were a wee mite resentful of him. But it may be that when he asked for active duty they wanted to protect him by giving him relatively safe duty on a battleship.

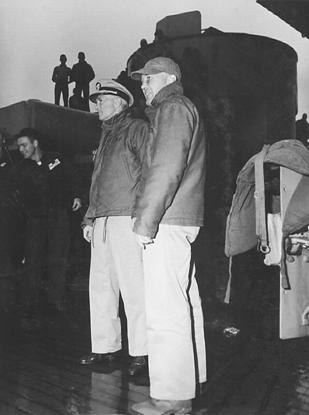

Rear Adm. Richard E. Byrd being welcomed aboard the

Alabama off the Japanese coast by the executive officer. (wearing the baseball cap.) The captain remained inside the conning

tower. The admiral had just removed

his life jacket after being transported from another ship by bosn’s chair. Admiral Byrd seemed a down to earth type of man. He

often went around talking to the enlisted men, listening to their gripes,

and where he thought they were justified he did something about it! With his outranking everyone on the ship,

he was much more effective than the chaplain! The galley prepared better food, we got

to eat some of the ham and turkey which, for some reason, had always been

saved in the food locker. When he

left the ship, shortly after the first atomic bomb was dropped, the food

reverted back to the previous menus.

Within a day or two of Byrd’s coming aboard, I had a rare glimpse of our captain. The admiral convinced him to leave the conning tower for a brief exercise period. The two of them walked back and forth at a brisk pace on the forward turret for fifteen or twenty minutes. This was repeated nearly every day while the admiral was with us. On most afternoons, for about an hour or so, the ship’s service gedunk stand would be open and men not on watch could buy a paper cup of ice cream. There was always a long line on the after deck when the stand was open. Beginning near the aft turret, it wound down to the deck below through one hatch and after the purchase was made, sailors would come back up on deck through different hatch. Admiral Byrd happened along, and seeing a seaman emerge from the hatch with ice cream, he called out to him, asking “ Son, where’d you get that?” The young seaman nearly froze from fright, thinking he was being called down for having the ice cream. He stammered that he had stood in the gedunk line to buy it, and pointed to the line on the other side of the ship. The admiral thanked him and went over to stand in line with the enlisted men. Such behavior from any officer, let alone an admiral, was unheard of, and certainly endeared him to the crew of the Alabama. I’m sure he could have snapped a finger at a mess steward and had a gallon delivered had he been so inclined.

I came into close contact with him myself when he requested having some pictures made. He went through channels and the navigator/photo officer told Reagan of the request, which Reagan was reluctant to handle, so he convinced me to do it. We arranged to have the guns in #2 turret elevated as a backdrop while he posed for me on the forward turret. He told me he needed the pictures “to show my goddamn friends back in the states what I’m doing out here.” The ship had just made a turn, forcing me to shoot against the light, so I elected to use flashbulbs to fill in the shadows. On about the second exposure, my flashbulb exploded, sounding like a shotgun, it showered the admiral with glass, and I think I jumped higher than he did. We were taking a small amount of spray over the bow, and I think a drop of moisture on the bulb made it blow up. I didn’t know how he might take it, and was worried. But, he just sort of shook himself off, brushed away the glass particles, and said, “Son, do you really have to use those flashbulbs?” The remaining pictures didn’t have flash fill! I talked with him again, the day after the atomic bomb had been dropped, when we were just learning a few of the details. He was enthusiastic about future peaceful uses of atomic energy. He told me he very much wanted to go back to Antarctica, and that he felt there might be deposits of uranium there. He did in fact get another expedition together not long after the war was over, but I never heard of any uranium being found.

During July and August, the task force was very busy, ranging up and down the coasts of the major Japanese islands, even venturing into the inland Sea of Japan to hit naval bases at Kure and Kobe. Three battleships, the Haruna, Hyuga and Ise, two heaavy cruisers, Aoha and Tone, and a fleet carrier, the Amagi, were sunk and two other carriers were damaged. Northern Honshu and Hokkaido were beyond the range of B-29 bombers, had never been attacked before, but carrier aircraft hit them now. 1391 sorties were flown, doing heavy damage.

Admiral Byrd on the forward turret of the USS Alabama,

July 1945

On July 18, a task force of battleships, cruisers and destroyers went in to bombard Hitachi on the coast of Honshu, about 80 miles north of Tokyo. I remember the date well because it was my brother Don’s birthday. (By odd coincidence, D-day in Europe was my birthday, D-day at Okinawa was my father’s birthday, the Yamato was sunk on my sister Pat’s birthday, and the fleet was anchored just outside Tokyo Bay on my mother’s birthday, the night before invading Japan.) This battle group included the battleships Iowa, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Missouri, South Dakota and Alabama. In addition, we were joined by some British units. Their battleship, King George V, was just behind the Alabama when we made our run in toward the coast. Since we were leaving the rest of the task force and were out from under the umbrella of air cover, there was a lot of apprehension over the possible kamikaze attacks. I always felt a certain amount of anxiety when heading into action and it was the normal reaction of nearly everyone. It has been said that if you weren’t scared silly by the kamikazes you might be just as crazy yourself. I had noticed that my partner Cathey didn’t seem to be affected much when going into action. When I asked how he managed to remain so relaxed and apparently calm, he let me in on a secret. He was using morphine! Months before, when the Randolph took the kamikaze hit at Ulithi, he saw a first aid locker open and unattended on the Bennington’s hangar deck during the confusion after the attack. He had scooped a lot of morphine syrettes into his musette bag. He offered to let me have one, “to try”. Despite his statements that he wasn’t addicted and that it wouldn’t hurt to try, I felt I’d rather be nervous and scared than use morphine. He was squeezing the syrettes out into his mouth to avoid having any tell-tale needle marks!

Running at 29 knots, the Alabama races

toward the Honshu coast for bombardment of Hitachi, July 18, 1945.

The bombardment of Hitachi took place near midnight, in a light drizzle. From my battle station at one of the 20 mm gun mounts about halfway up the superstructure, there was nothing to see except the blinding flashes from the muzzle blasts as all nine guns fired simultaneously. Although the maximum range of the guns was 21 miles, I believe we were only 12 miles out when the firing commenced. The ships moved along a line parallel to the shore as they fired. At a predetermined point, the head of the line turned toward the shore, moving in a wide U-turn, while the ships behind fired over the leading ships. This serpentine maneuver was repeated with the ships firing continuously until we were within just a few miles of the shore. I don’t remember exactly, but I think we were only six, or perhaps four, miles off when the bombardment was finished. There were six industrial targets. Targets assigned to the Alabama were a copper refinery and a steel rolling mill. She fired 270 16-inch shells that night, with most of the nine-gun salvos less than a minute apart. I had been told to hold my mouth open at the firing signal in order for the air to escape my lungs when the concussion struck. I found the shock wave so strong with six guns ahead and three behind, I couldn’t keep my mouth closed if I tried. The ability to find and hit those targets so rapidly in the black of night seemed miraculous. It was the culmination of centuries of evolution from primitive shipboard cannon into a nearly automatic 16-inch rifle with the miracle of radar added on. The lighthouse at the entrance to Hitachi’s harbor made a perfect radar reference point for calculating offsetting angles and distances to the nearby targets. It also provided precise location of the ships with respect to the shore. The fire control computers in use at the time, although crude by today’s standards, solved the complicated math problems quickly.

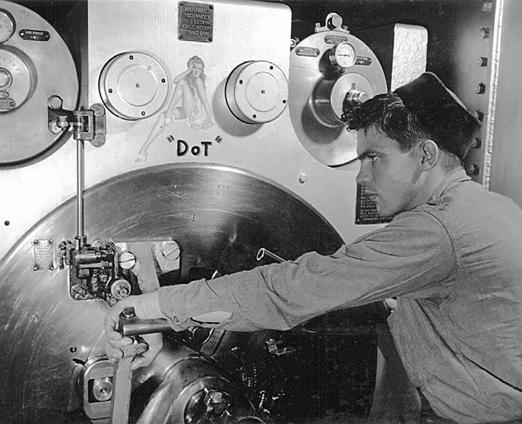

Gunnery crew cleaning the bore of one of the big 16-inch rifles.

The bombardment lasted less than an hour, but getting the ship back in shape took much longer. Damage control crews had to work on pipes which had broken loose and were leaking. Water was ankle deep in the head when I went down there after the firing was over. There was soot everywhere topside deposited from the burning powder charges and the bags that had contained it. Each shell fired actually moved the lining inside the gun barrel a tiny amount. When enough firing had taken place, the liners protruded out of the muzzle so far that the guns needed to be replaced. The gunnery crew took measurements to be sure that the liners were still within useable tolerance. I had a chance to examine aerial reconnaissance photos showing the obliterated targets a few days later.

During some heavy weather, a man on one of the destroyers was thrown hard against a gun mount, breaking both bones in his forearm. The muscles had contracted, pulling the broken ends past each other. He was brought to the Alabama’s sick bay to have the bones set and I was asked to photograph the procedure. The doctors thought they might have to cut the muscles, and had all their tools sterilized and ready. They had me dress in surgical gown, with mask and all, to do the photos. Injecting the patient with sodium pentothal, they decided to try stretching the muscles enough to set the break without cutting. The doctor and a corpsmen tugged with all their might, and finally succeeded. The doctor held it in place while an x-ray was made and as soon as that showed the bones were in proper position, a quick-setting cast was put on. I didn’t have to shoot any cutting!

Loading

a practice bag of powder into the elevator from deep inside #3 turret. Three such bags of cordite from the

powder magazine are loaded behind the projectile. Both the powder charges and projectile

are rammed into the breech by the same semi-automatic mechanism. The

practice bags used for drill were equal in size and weight (I think I was

told 90 lbs,) to the ones containing actual powder. The individual grains of powder were

about a half inch in diameter.

To round out our coverage of life on a battleship, we needed to show the inner workings of the big gun turrets. We had to get permission from the gunnery officer, who cautioned us not to bring any electrical cords or flashbulbs into the powder magazine. The gun crews went through complete firing sequences for us and we were able to get both stills and movies of every thing except the powder magazine itself. There were fireproof doors around it, so there were no chances taken. This took several hours of set-up and actual shooting, and after we had removed and packed up our equipment, we were ordered to report to the executive officer’s office. Apparently someone must have mentioned that we were inside a turret with cameras, and he didn’t like that at all. He gave us a scathing lecture about photos of classified material. He told us these guns operated faster than any others in the world, and even our British allies had never been allowed to see inside. I was sure we were about to be put into the brig. When he finally paused

Inside the turret’s

18-inch armor, the gun captain is ready to open the breech block. He has named the gun for his girl, with the

calendar pin-up picture to remind him of her.

He said when the gun heated up during firing, the picture

would come unglued and fall off.

for breath, Cathey was able to interject “But sir, if you would look at our orders”. The commander scornfully said, “orders, YOU have orders?” We both said, “yes sir, we do, from CINCPAC.” Absolutely incredulous, he called a yeoman in to hunt down those orders! He hadn’t simmered down very much by the time the yeoman laid our orders on his desk. Reading through them, his attitude shifted very slowly. At last he said, “Oh, I see here, your pictures are to be sent to CINCPAC, I suppose they will be sure they are properly classified.” Abruptly, we were told we could leave. Based on that episode, I didn’t hold a very high opinion of the Exec. But now, I think he was a good officer. Maybe a bit more of a martinet than necessary, but he was doing his job and most of the captain’s too, a lot of responsibility without the credit he probably felt he was due. The ship performed its job with efficiency and the kamikazes had never managed to hit her. There was only one serious accident while I was aboard. An electrician was working on a large electrical panel on the main deck. Wearing an aluminum hard hat of the type used in construction work, he leaned in, the hat made contact with high voltage and he was electrocuted. He was buried at sea the next day with the customary ceremony at the starboard side of the aft main deck.

The chaplain conducted the service and the bugler blew taps beside the flag-draped stretcher holding the body in a weighted canvas bag. Then one end was raised and the bag slid out from under the flag and rapidly disappeared beneath the waves.

After the gun fires, the

gun captain wipes away any burning bits of powder bags or sparks from the

mushroom head of the breech block using an asbestos protector over his left

sleeve. At the same time, his right hand

uses compressed air to blow out any sparks remaining inside the barrel of the

gun. If a tiny spark were to ignite

powder while the gun was being reloaded an internal explosion inside the turret

would be disastrous.

While some of the battleships, cruisers and destroyers were running in to bombard Hitachi, the carrier planes attacked the Tokyo and Yokohama area, concentrating on the Yokosuka naval base. These aerial attacks continued as the task force ranged up and down the chain of Japanese home islands. During strikes made during July 29-30, there were 12 merchant ships and three small naval vessels sunk in attacks on the northern coast of Honshu and at the Maizuru naval base on the Sea of Japan.

Alabama crew

members watching planes returning to the Essex after raids on Tokyo. July 1945

To most of the young sailors in the Alabama’s crew, duty on an aircraft carrier seemed glamorous. They didn’t understand that the noise, fumes and other general discomforts made the glamour disappear quickly once you were aboard. I personally thought battleship duty about the best of all the ships I had been on. That 18-inch belt of armor made me feel safer, even though I was not inside it! Perhaps the biggest disadvantage was due to its size. Because of the large number of people involved, as on the large carriers, there was more regulation than found on the comparatively free and easy life on a smaller ship.

When the Alabama was first put into service, a famous professional baseball player, Bobby Feller, was a crew member. He was no longer aboard when I was there, but his influence remained. Many of the crew practiced their techniques on the broad after deck. With the ship’s beam at 100 feet, not too many balls went over the side. The photo on the following page shows one ball player trapping the ball in his glove. In the same picture you can see the gedunk line headed for the hatch leading to the ship’s service on the next deck below. This was the line Admiral Byrd chose to buy a cup of ice cream.

Baseball practice and the gedunk line.

Crew members told me of another sailor who was no longer on the ship. He was known as “Clean Living”. Whenever the ship was in port, this man would spend his liberty drinking and carousing. On board ship, he kept a poker game going when he wasn’t on watch or asleep. Strict regulations against gambling were circumvented by holding the games in a cramped space with only one entrance. Lookouts were posted to warn of any approaching officer, so that the cards and money could be quickly hidden. Clean Living carried on this way for many months. Always in trouble, he was broken back in rank to Seaman 2nd class, but had never been caught running the gambling which the captain knew he was doing. Finally the captain checked the records of the Post Office, finding that hundreds of dollars worth of money orders were being purchased by this man every month. Confronting him with the records, the captain tried to get a confession. “Look at this. You’re sending more money home every month than I am paid. Where do you get it if you aren’t gambling?” Clean Living said, “Sir, I’ve been saving money ever since I was a little boy!” In frustration, the captain had him transferred to shore duty at Espiritu Santo. Those who had spent time there considered it to be one of the worst of the South Pacific hell-holes. It is in the New Hebrides at the eastern edge of the Coral Sea.

Listening to Tokyo Rose on the short wave radio in the crew’s quarters.

Tokyo Rose continued broadcasting propaganda stories about how we were being beaten by the victorious Imperial Japanese Forces. A few days before the first atomic bomb was dropped, one of our own broadcasts, repeated over and over to the Japanese, warned that several previously unbombed cities would now be targeted and destroyed. One of the ones named was Hiroshima. I suppose they thought this was propaganda too, for they apparently took no precautions and did not evacuate. Of course, they couldn’t realize the amount of utter destruction possible from just one bomb. I think we also had a hard time realizing how powerful it was. Finally, after the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, the surrender became a reality. It was announced to the fleet early in the morning as we cruised near the Japanese coast. The short wave radio now broadcast the sounds of revelry in San Francisco where people were celebrating. Later that same day one of our destroyers was hit by a kamikaze. We went alongside to try and help. Its smoldering hulk still floated, but the whole superstructure had been blown away and smoke was still drifting up from the compartments below. I saw no one alive. The men who died on that ship never had a chance to celebrate the war’s end. The irony and bitterness I felt from hearing people celebrate while we still were taking casualties stayed with me for many years.

When the announcement of the surrender was made, my partner, Jack Cathey, pulled off his helmet and threw it over the side. A bosun’s mate immediately threatened to report him for destroying government property!

Another anecdote passed on to me by the navigator happened that morning. He had been in the wardroom having coffee with several other officers when the exec came in. One of them slapped the exec on the back and gave him a cheery, “Good Morning”. The exec gave the other officer a stony stare and asked, “What’s so good about it?” Apparently the exec felt his chances of being promoted from commander to captain had vanished with the war’s ending. He was the only person I heard of who wasn’t very happy to have it finally end.

I think it was on the following day that Admiral Halsey gave a short speech to the whole task force. There may have been a congratulatory “Well Done”, but the part I remember was his reminder that even though the war was over, we were still in the Navy, and there were duties to perform. He ended the talk with, “Remember, a clean ship is a happy ship.” The bosun piped and the call "clean sweepdown, fore and aft" came out over the loud speaker system.

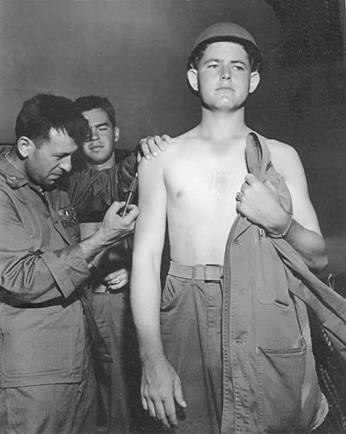

Since the war had ended somewhat unexpectedly, there was no large expeditionary force standing ready to occupy Japan. Because Task Force 38 was operating just off the coast, the fleet marine force was transferred from the various ships to a troop transport for the initial landings. Cathey and I were transferred to that transport along with the Alabama’s marines. Our assignment was to cover the first landings on Japan scheduled to take place on the 28th of August. While we went with the marines, the rest of our unit gathered on the Bennington and prepared to fly in from that carrier after the airfield was determined to be secure. We didn’t know what might lie in store for us upon landing. While there was no particular resistance expected, there might be some pockets of fanatical resistance. The kamikaze attack on the destroyer after the surrender declaration was reason enough for wariness. On the transport, the marines and anyone going ashore got fresh immunization shots. The marines gathered bandoliers of grenades along with their small arms, Cathey and I had our cameras and Colt 45’s. The photos on the next page show the transport coming alongside the battleship South Dakota to add its marines to those already aboard as well as the unique two-man bosn’s chair the South Dakota used for personnel transfer.

Troop transport ship approaching

the South Dakota. Marines

coming from the South Dakota.

New shots for the

marines. Note the expression on the

face of the man next in line.

When the troopship had collected the marines and everything was ready, it moved into Sugami Wan with other parts of the fleet and anchored for the night. Sugami Wan is a large open bay just outside of Tokyo Bay with a great view of Mt. Fujiyama. I will always remember the date, because it was my mother’s birthday.

At anchor in Sugami Wan August 27, l945. The

battleship Iowa and other ships of the occupation fleet are silhouetted by the

setting sun behind Mt. Fuji.

Early the next morning we entered Tokyo Bay and prepared to land. The Higgins boats were lowered to the water and cargo nets were rigged on the sides of the ship so that the men could climb down into the boats quickly. The landing site was the large Japanese Naval Base at Yokosuka, just south of Yokohama. We had been told that we should not even have clips of ammunition in our weapons unless we were fired upon. We weren’t expecting to be fired at, but I saw a lot of bullets loaded as we approached the beach. Marines who had been in combat in the Pacific had little trust in our now former enemies. I too loaded my 45 automatic pistol. I was in the third boat to pull away from the ship and we maintained that order to the beach. But first we had to circle around near the ship while the other boats finished loading and joined the group. The weather was calm.

Higgins

boats full of marines circle while waiting for the rest of the boats to be

loaded. The morning of August 28, 1945.

Marines get down in the boat as we approach the

landing site. The navy coxswain

running the boat and I remained standing.

There is a B-29 overhead (just behind the caxswain’s helmet) as we

pass by the last remaining but damaged Japanese battleship, the Nagato. It

had been their flagship in the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

The landing went very well, the boats came up on a seaplane ramp, and I only got one foot wet! I was very busy for the next few hours. I climbed up on a radio tower to get a good view of the second wave of marines coming in. With the usual shots of marines coming ashore, there was a lowering of the Japanese flag and the raising of ours, and by noon there were one heck of a lot of U.S. marines on the Yokosuka Naval Base.

The second

wave of marines about to land at Yokosuka,

August 28, 1945.

There were a couple of isolated individual acts of fanatic resistance. One involved a man in a cave where explosives were stored. He was killed before he could set off the whole thing. Most of the base was empty of personnel, except for a few who were as wary of us as we were of them. Most of the people who had been assigned there had gone elsewhere. I don’t know if they had been allowed to go to their homes, but I believe they did, from what I saw of the male population later. They all seemed to be wearing uniforms, but obviously were no longer in service.

As planes from the carriers came in, we were soon joined by other photographers, not only from our unit but from all others who had been in Task Force 38.

Marines continue coming ashore

at Yokosuka, August 28, 1945. A B-29 can

be seen flying overhead.

As photographers, we were interested to find that the Japanese navy’s photographic training school was at Yokosuka. It was their equivalent to our Pensacola. The combat photographers made this their headquarters, and we were able to make use of their darkrooms and some of the equipment they had left.

This was the only time I had to live on K-rations. They came in a wax-covered olive-drab box like a cracker jack box. Inside were very dry and hard cracker-like biscuits, a can of eggs and chopped spam, some instant coffee and a chocolate bar. Given enough water, it could make a meal, but after a few days of this, not so wonderful.

Out behind the Photo building, there was a large smoldering trash heap. Apparently all manner of things had been burned just before we arrived. But on top of the pile, as though an afterthought, pieces of a torn-up photograph had been added after the fire was no longer hot. Grant Hayes, being of a curious nature, wondered about this and set out to put the pieces back together like a jig-saw puzzle. Working together, we soon saw a photo of Pearl Harbor under attack! A day or two later we used a Japanese view camera and one of their glass plates to make an 8x10 copy, and then printed it in their darkroom

Copy

of photo made by an unknown Japanese photographer while Pearl Harbor was under

attack,

By mid-afternoon on that first day ashore, it appeared that there would be no organized opposition to the occupation. My friend Baker suggested that he and I take a walk to “see what’s on the other side of that hill”. The hill he had in mind was outside the base perimeter. When we got to the perimeter gate a marine told us we couldn’t go beyond that point. This was as far as the marines had secured the area. We showed him our fleet camera passes which carried Admiral Nimitz’s name. The marine said “OK, go ahead”. What we found on the other side of the hill was a picturesque little village. We saw lots of people in the street. A policeman in black uniform with his long two-handed sword stood in the center of the road about a block from the edge of the town. We couldn’t converse with him, as he spoke no English and we had yet to learn any Japanese. He was nervous, but didn’t try to stop us from going into the village. As we walked on, a big change took place in the village. The streets emptied, blinds went down over the windows, and we could almost feel the people peering out at us from inside. There were two small boys who had stayed outside seemingly too petrified to move. We approached them, and with sign language got them to accept some chewing gum. I wondered if their parents would let them chew it. Obviously the people here were scared to death of us and we began to feel uneasy about our little expedition. All we had with us were a couple of cameras and my 45. If there had been any trouble, we were hopelessly outnumbered. We went back the way we came, being cordial to the policeman in passing. We found out later that we were the first westerners ever to enter the village of Yokosuka. It had always been kept off-limits to foreigners.

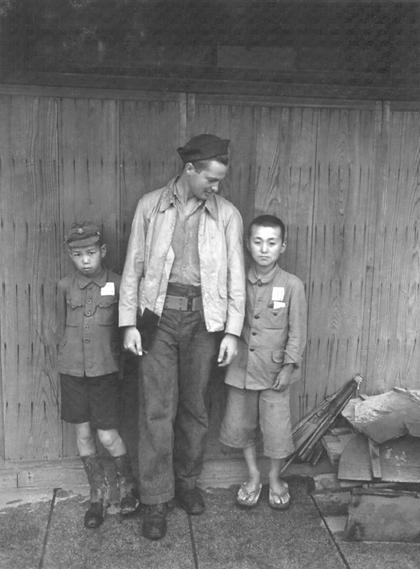

Yokosuka boys, August 28,1945. Photo by E.R. Baker.

Back at the photographic building we noticed that the second floor had a roomful of bunks, all made up, complete with white sheets and a curious type of long narrow pillow, folded double inside a clean white pillowcase. These looked

Higgins and Helton in the bunkroom with k-rations, Jap

rifle and cigarettes. Note that the windows had been taped to stop broken glass

from flying around during air raids.

pretty good to us even if the bunks were a bit short for the taller men. When we finally turned out the lights everyone began a new experience. Fleas. The straw ticks were loaded with the little bugs, and boy oh boy, did they have a bite! Luckily, someone located a can of DDT powder, and a liberal dusting on each straw tick mattress solved the problem. They flew out in clouds. Even so, everyone was flea-bitten, and busy scratching the bites. I still had sores on my legs when I finally got home on leave for Thanksgiving about three months later.

For quite a long time the Japanese had not been able to get regular supplies of petroleum. The few vehicles that were running were burning either alcohol or carbon monoxide generated from large canisters of charcoal carried on the rear of the bus or truck. No private cars were being used at all. All gasoline was reserved for aircraft. Needing some means of transportation, and with Mr. Rogers’ consent, we confiscated an alcohol fueled tanker truck. We found its performance very poor, so one of our mechanically inclined members put aviation gas in the tank, did an adjustment on the carburetor, and we were off to see the sights!

Guttosch, Branson, Higgins, Brunton and Lt. Rogers with our “personnel carrier” outside the Yokosuka Photographic building we used for our headquarters in Japan.

Entrance hall

inside the Photographic Training School building.

While we now had transportation and could roam away from the base, we still had assignments to do. There were many interesting things to photograph and document right on the base itself. Kamikaze pilots had trained there, and there was a shrine to their memory. By the time I found it, the marines had already been there, and had smashed most of the interior. It contained photographs of the pilots, displayed under glass, but much had been destroyed. Also, there were some of the baka bombs. Fortunately I hadn’t seen one close up before!

Photo from the shrine to

kamikaze pilots. In the photo below , I am

standing beside a baka bomb. It was powered by a rocket engine and carried

2000 pounds of TNT in its nose. It

was designed to be carried by a “Betty” twin-engined bomber within rocket

range of its target and then released on its one-way trip.

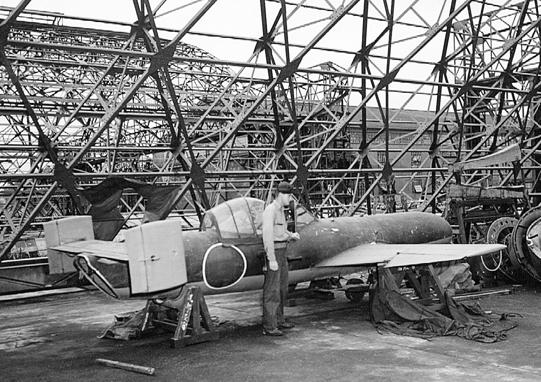

A Zero and some

Betty’s at the Yokosuka air field.

Surrender terms

required propellers to be removed.

Experimental jet fighter. It didn’t get into production and so far as I

know, never was flown.

On September 30, 1945, after Yokosuka was considered secure, one of our cruisers, the USS San Diego, CL53, became the first US ship to tie up at one of the Japanese Navy's docks there.

A Japanese work party with US Marines and Navy personnel in charge, assist with docking preparations as the ship approached.

One of the most interesting assignments I had while in Japan was photographing the battleship Nagato. Another member of CPU#6, Davis, and I went from stem to stern to document the damage it had sustained and the many differences from our own ships. At that time I was unaware that the Nagato had been Admiral Yamamoto’s flagship during the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was the last remaining battleship of the Japanese fleet, and was later taken to Bikini for the hydrogen bomb tests.

The Nagato at anchor in

Tokyo Bay. She had suffered considerable

damage from our air attacks, and was no longer seaworthy. Some compartments were filled with water, and

she had a slight list.

This ship used sound detectors, as the Japanese had no radar. Communication from the bridge was through speaking tubes, and I thought its design to be pre-World War I. Inside the 14-inch gun turrets, it was obvious why the executive officer of the Alabama had been so zealous in guarding information about ours. Here the shells were stored in bins, laid horizontally like cordwood, and had to be manhandled with block and tackle. It would have been interesting to compare its firing rate with the 45-second interval between nine-gun salvos on the Alabama. An acquaintance whose destroyer came under its fire in the Philippines said that they were saved by the relatively long interval between salvos. They were bracketed several times, but each time they could maneuver enough to avoid the next one. The destroyer’s higher speed eventually took them out of range.

Some of the Nagato’s crew being addressed by their

commander as they are about to leave the ship. Note the rising sun flag in the

upper right corner of the photo.

The prize crew from the USS Iowa has lowered the

rising sun and raised the stars and stripes just after coming aboard the

Nagato. The Japanese flag is being

folded by the men on the right of the photo.

End of Section 4

See Section 5 to continue with War Stories