War Stories by Lyle Hansen, Copyright 2002

Section 7

Japanese commanders of Truk arrive alongside the

General Mugikura and Adm. Hara coming aboard . General Blake leading the

wardroom conference. The Columbia’s

photographer is in the background.

The Japanese commanders were invited out to the Columbia for a conference

before the landing party went ashore.

They offered to guide the ship in through the minefield so it could be

at a dock. The skipper said no

thanks. He saw no need to take that

risk, as the Higgins boats on deck had

been brought along to transport the inspection team members. Some time was spent in trying to determine the fate of our aviators lost in the raids over Truk. The answers given were that all had perished when their planes went down. After that, an agreement over details of the inspection procedure was worked out.

The

Japanese side of the conference table in the Columbia’s wardroom. Interpreters

standing, Admiral Hara in white uniform.

One of the

three Higgins boats bringing the landing party inside the lagoon.

The morning after the conference the Japanese came back to guide our party ashore in the Higgins boats. (Official designation of these boats is LCVP, which means landing craft, vehicle and personnel.) There were twelve marines, the two photographers, the general and members of his staff, Navy Medical personnel and the captain of the Columbia. Navy coxswains ran the boats and a Japanese navy man came along to show the way through the mines. As we entered the mined area, a sudden rain squall came up reducing visibility so that our guide couldn’t see the landmarks. He became nervous and then very agitated. At first, with the language barrier, no one understood his problem. It turned out that his chart of the mine locations was missing. The boats were ordered to orbit in a tight circle. One of the young marines had picked up the chart, not knowing what it actually was, and decided to keep it as a souvenir! It had such nice Japanese characters all over it. As we continued orbiting in that tight circle, it became obvious who the culprit was. His face turned turned a brilliant crimson, and he finally reached up under his tunic and brought out the missing chart. The rain squall passed, and we proceeded on into the lagoon. There were many sunken ships, some with masts still above water, and in places we were so close to mines that they were visible just below the surface.

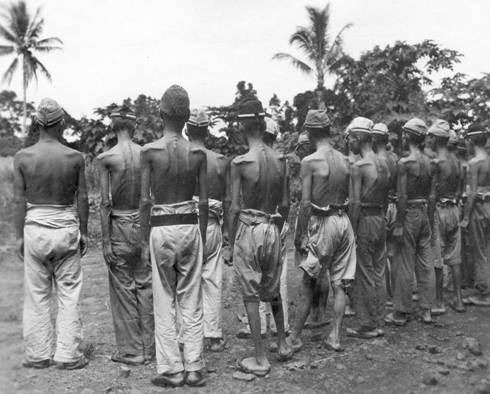

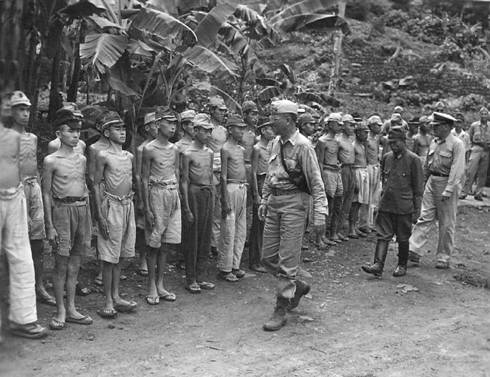

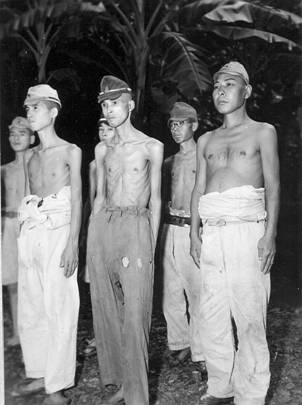

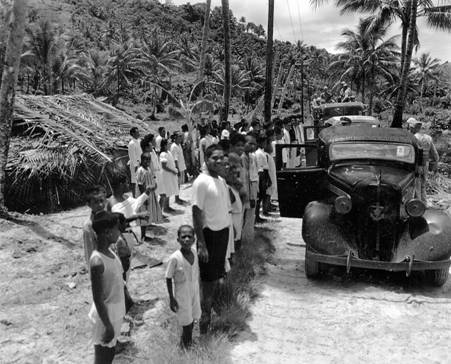

After landing on one of the main islands, we toured the installations by motorcade. The soldiers and sailors were lined up in formation for the inspection. General Blake had asked that the military personnel be assembled with their shirts off so he could see if they were really undernourished. There was no doubt of it, as you can see in the pictures on the following pages. We also visited a number of the native villages. There were approximately 10,000 natives in addition to 40,000 Japanese. The native population had apparently been treated reasonably well. They grew their own food, patches of yams, alongside each hut. Coconuts and bananas seemed plentiful, and they didn’t look undernourished. Their main complaint seemed to be that since the lagoon had been mined they weren’t allowed to fish from their canoes. I spoke with one of the village chiefs who knew English. He was an elderly man, and proudly told of sailing to San Francisco on a trading schooner when he was young. I asked him what he thought of San Francisco, and he said, “too many horses, too many people!”

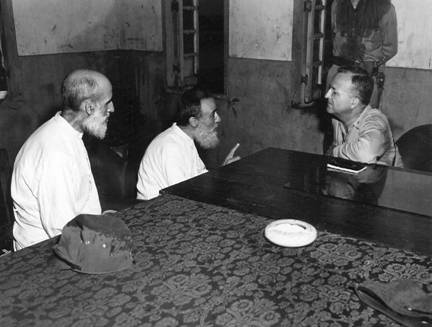

There were

two Spanish priests ministering to the native population.

General Blake conversed with them at some length. He spoke fluent Spanish, having been in

Nicaragua during his career in the Marine Corps.

My photo partner Grant Hayes walking past the Japanese Admiral’s staff

car as the

motorcade got ready to depart the Naval headquarters.

Motorcade inspection of Japanese personnel .

Physical

condition of the military personnel.

USMC General Blake

accompanied by Lt. General Mugikura, Imp. Japanese Army, and the captain of

the

cruiser Columbia, during

inspection of the Japanese personnel at

Truk, early October, 1945

.

Starvation

closeup.

General Blake talking with the Spanish priests.

The inhabitants of the villages lined up for

inspection. They were in good health,

other than a few instances of common tropical diseases such as yaws.

The women were dressed in their

Sunday best.

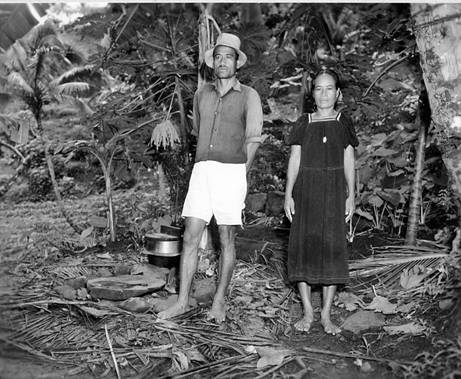

A successful fishing trip to the reef by this couple

with their catch of an octopus. Below - The chiefs of the

villages on one of the islands were at the dock when we came in.

.

I can’t recall the names of all the islands we toured, two that I do remember were Dublon and Moen. We returned to the ship each night, but got very little sleep. We had to process the film and make prints, a set for each officer in the team of inspectors! The Columbia’s photographer had a small darkroom that we were able to use. Here, just above the equator, the water temperature was about 90. We were obliged to use seawater to wash the hypo from negatives and prints and then finish removing saltwater with a small amount of fresh water from the ship’s evaporators. Care had to taken to avoid reticulating the film’s emulsion by keeping all solutions at the same temperature. It was usually two or three in the morning before we could get into a bunk for a few hours rest before reveille.

When we were at Admiral Hara’s headquarters he served a shot of Scotch whiskey to each of us and followed up with tea. The scotch (from Suntori Distilleries in Japan.) was good, but the tea was unlike any I had ever tasted before. It was nearly colorless, and had, I thought, a faint fishy flavor. One of the men serving tea spoke English. I don’t know his rank, but in our navy he would have been a steward’s mate. I found that he was from Vancouver B.C., where he had been a truck farmer. He had gone back to Japan to visit relatives and was drafted into the military. He had been at Truk for about four years, and was hoping to get back to Vancouver. He said, “Truk is very hot prace”. The frequent air raids from our aircraft carriers during the past two years had been destructive, and no supplies got through the blockade for eighteen months except for what a submarine brought once, a year earlier. Before we left, each officer was presented with a Ceremonial Short Sword as a souvenir. These were hari kari knives, a part of the Japanese Naval Officer’s dress uniform,. We enlisted men were given a plain type of samurai sword like the ones the police in Japan carried. Grant Hayes and I decided to catch up with the main group a bit later and went to see the Admiral after the others left. He spoke English, and graciously provided us with two of the ornate Short Swords. The handles were covered with seed pearls, and the blades were inlaid with cherry blossoms done in red gold. I’m sorry to say I sold both it and the big two-handed sword on my way home. I got $125 for the hari kiri knife, and $75 for the big sword. (The money was needed to help in construction of the home my wife and I hoped to build.)

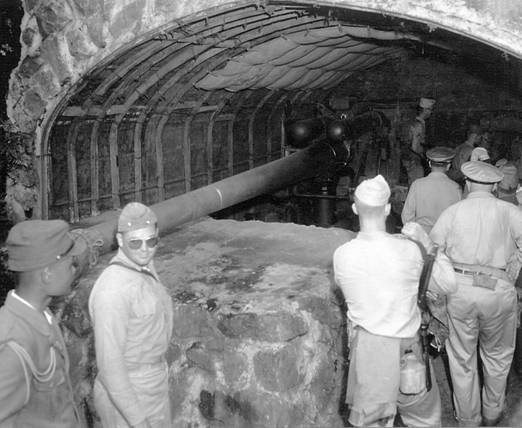

The military installations at Truk were quite extensive, and would have been strongly defended if we had tried to invade. There were carloads of mortars of the type so well used at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Munitions were stored in large caves beyond the reach of bombs or gunfire.

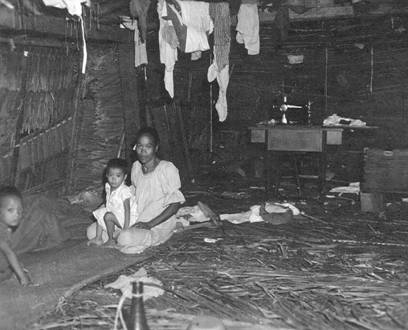

One thing I noticed was the difference and apparent rivalry between their army and navy. We had interservice rivalry, but here it seemed stronger. The navy hospital had beds. The army put patients on straw mats. If one unit had a bag of rice, it didn’t appear they would share with another.

Bath time for the baby.

Some of the younger children

wore grass skirts. The only real ones I

ever saw.

The youngsters are in the yam

patch beside one of the homes.

Cooking was done outside of the native dwellings, using pits lined with heated stones for baking or roasting. These people lived close to nature and seemed to be happy.

These folks are standing beside their outdoor

cooking pit.

This home

had a Singer sewing machine.

Practical solutions for the Truk climate. Food and shelter available, clothing minimal.

In general, the military were much worse off than the native population. They had been the targets of many air raids. Supplies from their homeland had been cut off for a year and a half. There were less than a half dozen bags of rice left for the whole garrison. They hadn’t been prepared for such a long siege. The smokers among them had run out of tobacco early on, some were growing and curing their own. Even so simple an item as matches were not to be had. I hadn’t realized this when we first went ashore. (I smoked cigarettes in those days.) They cost only a nickel a pack overseas where taxes didn’t apply, and while preferred a pipe I couldn’t get pipe tobacco that wasn’t moldy. At one installation I was about to light a cigarette and found I had used my last match. A young Japanese operating a switchboard was nearby, so I asked him, with sign language and bad Japanese, for a match. He tried to tell me there were none. Misunderstanding him, I thought he was trying to be smart. I reached down and touched my sidearm holster. He bolted from the switchboard and I thought I must have frightened him out of his head. After several minutes he returned with a glowing ember on the end of a charcoal stick to light my cigarette! I felt badly, but all I could say was thank you in very poor Japanese. Arigato! Later an aviation officer, a colonel as I recall, demonstrated his invention for lighting cigarettes. He had a box on his desk with a hand-cranked telephone magneto mounted on top. Turn the crank, a spark jumped between electrodes and ignited a wick in an aluminum tube that came from a bottle of gasoline inside the box.

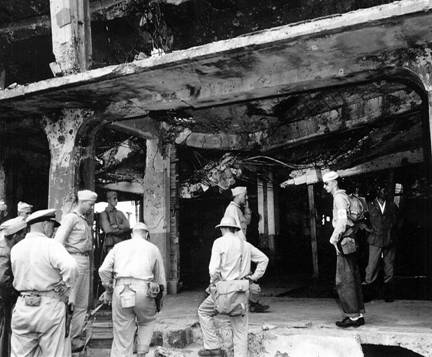

This reinforced concrete

building was the communication center for Truk.

From this view it appeared to have withstood the bombing very well. Only a few pock marks. Probably due to strafing from 50 caliber guns

on our aircraft.

But from

the other side, not so good. Portions of

the buillding were still in use. The

radio plea for

help was sent from here.

Looking at the damaged

Communication Building. The man with the

armband was a hospital corpsman with the medical officers in the team.

Bomb crater on the runway of an

airfield. I think it was on Dublon. One of the doctors was looking to see if he

could find malaria mosquito larvae.

Evaporating sea water to make salt

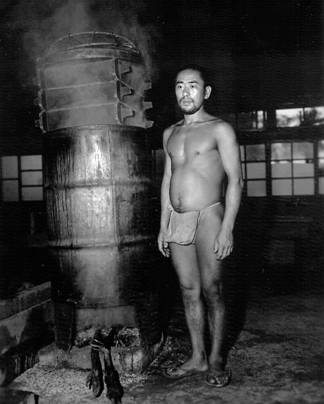

This

man, a Japanese civilian, was tending a fish smoker. While the natives couldn’t fish because

of the mines, the Japanese did fish and supposedly shared the catch with the

natives. There was a cold storage

facility, only partially destroyed by bombs, where some of the large sharks

were frozen and stored. A band saw

was being used to cut steaks about two inches thick when our inspection

team was shown though. The sharks were frozen whole without gutting. I

don’t know what happened to my photos of the frozen sharks.

Cook in a

Japanese navy kitchen at Truk. Tobaco is drying over the stove.

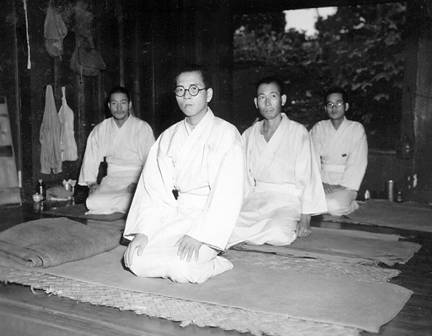

Patient in

the naval hospital and a hospital corpsman. Someone gave the corpsman a U.S.

cigarette.

The medical

team examining a patient at the naval hospital.

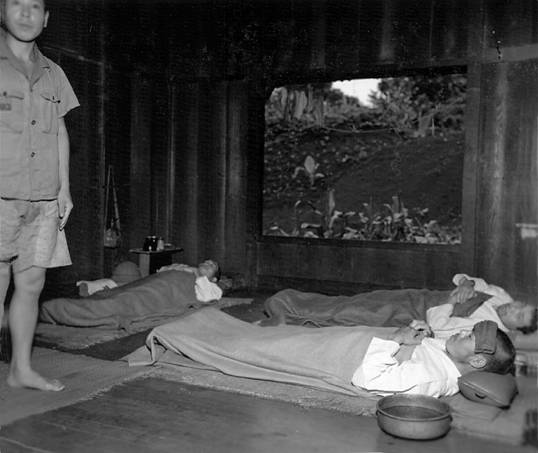

These men were patients in the army

hospital. Our shoes were sprayed with

carbolic acid before we entered. There was a case of ameobic disentery here,

and a skin grafting operatioon was being performed. From the way the poor

patient was screaming, I think they were out of anesthetic. Some of the more seriously ill patients are

shown on the next page.

Patients in the Japanese army

hospital.

General Mugikura’s office and quarters

were near the army hospital, as I recall.

The general was a small man, about five feet tall. His

headquarters had aparently been built to his scale. I failed to notice how low

the door frame was and banged my head on it.

It got a good laugh from the Japanese inside. The taller ones must have been used to

ducking down.

At the airfield with all its

destruction, one of the Japanese officers was telling a Marine colonel how bad

the air raids had been. There was wreckage all around, the runway was full of

bomb craters, a real shambles. The young

colonel had fought the island hopping battles from the Solomons up to and

including Iwo Jima, and he had little compassion. He said, “You think this was bad? Wait until you see Japan! I was just there, and it is really bombed

out. This is nothing.” The Japanese officer looked like he had been

hit on the side of his head. The marine

followed up by giving his version of how the Truk airfield would be rebuilt. “We’ll bring seabees with bulldozers down and

fill these holes. I think put in another

runway over there, need to make this one longer. We’ll have P-51s taking off

that way, B-29s over on that one!” His

audience’s head went from side to side, watching the imaginary takeoffs. I felt sorry for the Japanese officer. He must have been longing to get out of that

hot hell-hole for years, dreaming of home and peace. Now he’s told everything is destroyed.

There were three aircraft said to be in

flyable condition. They had been pieced together by canabalizing

parts from the wreckage.

The main airfield.

Looks like

what was left of a Betty. Floats for

seaplanes in foreground.

One of the flyable aircraft.

The inspection team at a cave where

munitions were stored.

Anti-aircraft gun emplacement.

These were the guns that gave our new pilots their first

baptism of fire when new carriers joined the fleet.

This anti-aircraft gun had been

mounted in a cave to serve as a coastal gun in the event of

an invasion.

After three days of inspecting all the

major Truk installations, the team had finished its work and was ready to

report back to CINCPAC. While they were

writing their reports, we still had film to process and prints to deliver. It was one more night of work for us. I spent the return trip to Guam trying to

catch up on my sleep. The Columbia was my only experince with cruiser

duty. It seemed to me that it had the

friendliness and comaraderie of a destroyer, but with some protective armor! Sea duty at its best, so far as I could see.

Back at CINCPAC things were winding

down. The combat photo units were

disbanding. Having been on assignment, I was one of few who still had camera

equipment. It was time to turn in all five of my cameras and the sidearm. A bit

like saying goodbye to old friends. I

had even grown to like the .45 Colt even though I had never fired it. The men

who had enough points to be discharged were moving to another location to wait

for transportation home. Mr. Rogers had

been working to get all the men in CPU #6 home as soon as possible. Those with

points, not many in this unit, were leaving.

The others he tried to place at installations near their homes. During the later part of October he told me

he had tried to get a billet for me at Sandpoint Naval Air Station in Seattle,

but found there were no openings. The

best he could do, he said, was to send me to Oakland Naval Air Station in

California. Of course I would have liked

to be in Seattle, but Oakland was on the west coast, and hopefully I would be

able to get home on leave. I was very

pleased.

My orders came through in November and I

moved to a barracks down near the harbor to wait for transportation. Being on

orders, I now had a priority to leave ahead of those men with all the

points!

While I was waiting to leave Guam, I met a man

who was trying desperately to get home. His mother was dying of cancer, and was

not expected to live more than a week or two.

He had tried every possible way to get transportation to no avail. Just a week or two before there had been

newspaper articles about the Red Cross getting a soldier in Europe flown home

under the exact same circumstances. So

he contacted the local office at Guam.

They told him they were sorry, but it wasn’t possible for them to

help. When he asked why they did it for

this soldier in Europe he was told, “Well you see, that was during our fund

raising drive, there’s just no way we can do that for everyone who needs to see

his mother!” This left a lot of bitter

feelings toward the Red Cross among all who heard the story.

The escort carrier Bogue.

I was destined to ride an escort carrier

once more to Pearl Harbor, but this time coming from the west, and with the war

over there was no reason to zig-zag. It

was the Bogue, the first anti-submarine carrier built. Her air squadron had sunk Nazi subs in the

Atlantic but was now a personnel carrier in the Pacific. I sold my Japanese

swords to two souvenir-hungry sailors on this ship. The picture of the Bogue

came from a Time-Life book, “The Carrier War”, and was credited to the courtesy

of Vice Adm. A. B. Vosseller, USN, (Ret.).

It took the better part of a week to get

to Pearl. We went ashore from the Bogue,

lined up and were inspected to make sure no one was bringing weapons or

government property with them. Every

third man had to empty his seabag for the inspecton. Then we, and a lot of other people boarded

the old Saratoga. She had been fitted

out to transport returning Navy personnel from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco, I

think seven thousand per trip. The

hangar deck was packed with pipe frame berths, stacked five high! Having been

built before the war, this ship was constructed differently than the carriers I

was familiar with. They were all steel

and paint. Here there were lots of

bronze fittings. It was really solidly

built. Steaming at flank speed, the trip took just three days and two nights. We stopped at the Faralon Islands to take on

a pilot to enter the Golden Gate. A

schooner brought the pilot out from the island, and what a beautiful sight it

was to see it come up under full sail. Some fine yachts were comandeered by the

government during the war, and I assume this was one of them. The schooner hove to on the lee side of ship

and the crew dropped their tender into the water. Four oarsmen rowed the pilot

to the ladder that was lowered for him.

With the pilot aboard the Saratoga, the

schooner took its tender onboard and sailed back toward the island as we got

underway. The entrance to San Francisco

Bay was soon visible under a bank of fog.

As we passed under the Golden Gate Bridge, the tops of the towers were

in the fog, but what a wonderful sight.

Home at last! Then on to Alameda,

where the big carrier docked. I expected

to be at Oakland NAS soon, since my orders were to report there. But no, a burly bosun’s mate ordered me into

a truck loaded with men bound for Treasure Island. I tried to tell him I was supposed to go to

Oakland, but he shouted in his Brooklyn accent, “Youse are going to Treasure

Island!” So out on the Bay Bridge to

Treasure Island I went. When I got

there, and tried again to find out how to get to Oakland, I found my orders had

gone directly there as I should have, but there was no more transportation in

that direction until the next day.

Treasure Island was so crowded with returning personnel, there wasn’t

space in the barracks. Finally I was

given a folding cot and blanket and allowed to sleep in the furnace room of one

of the buildings. One bright spot was

seeing pitchers of fresh milk in the mess hall.

The next morning I boarded a Navy bus for Oakland and received a fine

welcome as soon as my orders were processed.

Oakland NAS was the world headquarters for the Naval Air Transport

Service. NATS had been put together from

a nucleus of Pan American Airways personnel and operated more like a civilian

airline than a unit of the

military. I was immediately given two

weeks leave and put on a flight to Sand Point Naval Air Station in

Seattle. It was Thanksgiving Eve, and I

may have been the most thankful person in the whole world. Marie and our 17month-old son Steve met me at

the Sand Point gate, having been brought there by her father and mother for our

very happy reunion.

Two weeks of leave were over all too soon. While Naval Air Transport had flown me to

Seattle, there was no return flight available, so I took a Greyhound bus back

to Oakland NAS. It turned out that I and

another ex-combat photographer acquaintance, Bill Susoeff, were jointly in

charge of the photo lab, and we had one seaman striker to work with. The photo

officer called us to his office and explained that he was also the station's

operations officer as well as the legal officer for COMNATS. He said that unless we got into trouble, we

probably wouldn't be seeing him as he was quite busy. If we needed any supplies he would make sure

the requisitions were signed and sent on.

We were to make sure that one of us was always at the station, but that

we could keep our liberty cards and go to San Francisco or wherever we wanted

so long as we didn't both go at the same time!

We stayed out of trouble and never saw him again. The photographer I had worked for between

high school and college was now in business in San Francisco, so I visited him

when I could. Bill Susoeff was given a

weeks leave at Christmas and I drew a week at New Year's. My old boss had me

come to his home near Golden Gate Park for Christmas dinner.

The photo work at Oakland Naval Air

Station was mostly routine. Each week

several large status boards depicting the NATS activities and the location and

status of all aircraft in the system were photographed and reproduced for the

Commodore and his staff. (My

understanding was that NATS had the only Commodore in the navy at that time.) These were quite a challenge, since the data

posted on the boards was in form of movable plastic letters and numbers that

curved so that they produced reflections from any lighting that tended to

obliterate the information. A plane load

of parapelagic patients was brought in from the Pacific and I was called on to

picture their arrival and unloading from the plane. Reporters and photographers

from the wire services and the San Francisco papers were on hand as well. I recall being elbowed rather ruthlessly by

one of SF Chronicle photogs in his

efforts to get close to the patients. Whenever there was an accident of any

kind it was photographed for record purposes.

Once I went to Redwood City at the south end of San Francisco Bay

because of an accident with a Navy pickup truck and a civilian vehicle there. A

new system of landing airplanes in bad weather by GCA (Ground Controlled

Approach) was being used at the often fog-bound Oakland NAS field. I was asked to photograph a four engined

transport coming in from Hawaii using GCA. The fog was very dense. Visibility must have been near zero. I could hear the plane's engines as it circled the field, but nothing was

visible. Then as the engine noise grew

closer, the engines were throttled back and there was very little sound until

the screeching of the tires sounded on the runway directly in front of me. I

not only couldn't get a picture of it, I couldn't even see it!

During this period nearly every one wanted

to leave the military as quickly as possible.

The Navy seemed to be unable to keep the number of experienced pilots

that were needed.

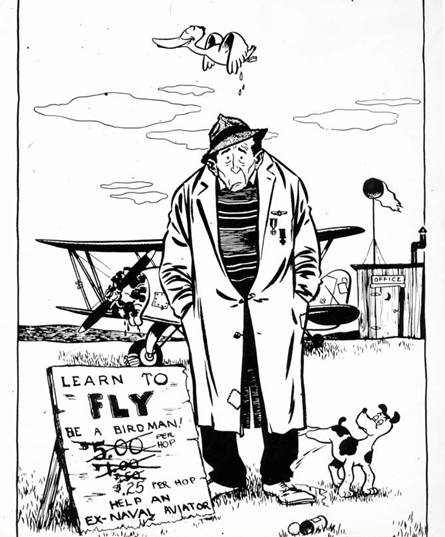

This cartoon was reproduced in the photo

lab and posted on the appropriate station bulletin boards in a humorous effort

to keep pilots from becoming civilians.

I too was anxious to go back to civilian life. When I first returned from overseas it

appeared that I would probably be in the Navy for another year in order to earn

enough points for discharge. However,

almost every month there was a reduction in the number of points required, and

by February of 1946 I had enough. I was anxious to get back to Seattle. My wife and I had bought a small acreage

north of the city before I went into the service, and I wanted to begin

building a home for our little family. The schedule called for me to go by ship

from San Francisco to a receiving barracks in Bremerton, Washington to be

processed for discharge. It looked to me

as though this would take up at least a week longer than if I took my discharge

in California. I was able to arrange for that and went to the receiving

barracks at Camp Shumacher. The pilots were not the only ones being encouraged to stay in the Navy. A Wave officer in the NATS personnel office

tried to assure me that if I stayed I would likely be promoted to CPO within 18

months and stay with NATS. When I

arrived at Shumacher (with a few hundred others from installations around the

Bay area.) the first order of business was a lecture from a grizzled CPO on the

merits of staying in. At the end of his

talk he asked for a show of hands of those who wanted to sign over. There were no takers. We were called back to

the auditorium later, this time for a lecture by a junior officer. He had no better luck than the chief. Finally, we got a third lecture, this time

from a commander. He was apparently more

persuasive, as he did get a couple of men to sign over. There was plenty of paperwork, and I was told

that because of the injury to my leg, I probably was elligible for some

disability payment. I was also informed

that processing a claim would take some additional days before discharge. I elected to sign a waiver to get out a

little faster! As it was, three days

elapsed before I was able to get my discharge papers. Then I went back to Oakland NAS. Through some

sort of miracle there was a plane due to depart for Seattle and there was room

enough for me to come along. The next

time I saw Oakland NAS, was about four years later. It had become the Oakland Municipal Airport,

and what had been surrounding farmland was covered with homes and apartment

houses. I sometimes wondered what might

have happened if I had decided to stay in the Navy. It seems doubtful that I would have advanced

to CPO so swiftly or that I would have been able to stay with COMNATS. Eighteen years later, when I could have

retired had I stayed in, I sometimes wished I didn't have to keep commuting to

my job every day.

Once back in Seattle, I concentrated on

getting a small home erected on our 2 1/2 acres several miles north of the

city. My father was a carpenter and

shipwright and he was of great help. I

began by clearing out the small trees that grew on the building site by hand

with an axe and a mattock. I had an

aversion about paying rent, and Marie's parents let us stay with them until we

could move into our new home. The plan

was to put up a double garage and live in that until we could afford to add a

house adjacent to it. In about six weeks

time, with only tar paper covering the exterior and the newly poured concrete

floor not yet fully cured, we were able to move in. Not all of the plumbing was

finished, but the tiny bathroom with shower was operable. We didn't have a car, as the auto companies

were still converting from war production, and new cars were unavailable, even

if we had the money to buy one. My dad

loaned me the use of his 1929 Pontiac on occasion, and Marie's father helped

with his 1939 Ford. There was a busline

within a couple of blocks from our building site. One day I had gone downtown

to pick up some plumbing fittings and I ran across a man I had worked with at

Boeing during the first part of the war. He asked what I was doing and I told

him about my home-building project and that I had been too busy to think about

what I might do in the way of a job. He said aren't you coming back to

Boeing? I was aware that all contracts

had been cancelled at the war's end and all employees were laid off. I had assumed the whole place had remained

locked up, but now I found this wasn't the case. I told my friend I wasn't quite ready to go

back to work and wasn't sure I wanted to be at Boeing again anyway. He explained that there were a couple of new

commercial models on the drafting tables, that the Engineering Photo Template

Unit was busy and that I could likely get my old job back. I wasn't convinced, but he did persuade me to

at least stop by for a visit.

Our home north of Seattle at N.180th and

Fremont Ave., as it looked when completed.

A few days later I went down to visit to

my former workmates at Plant 2. The

factory where more than 5000 B-17s had been produced was silent, but the

engineers were indeed busy. Arriving at

the administration building I told the receptionist I wanted to visit Mr.

Pirogoff who was still in charge of Engineering Reproduction. When she called him he immediately came out

and took me to his office. He spent some time asking about my military service,

and almost before I realized what was happening, he sent me to the personnel

office and I was rehired back at my old position of Photo Template

technician. This was fortunate, as our

meager savings had been nearly expended on home-building materials.

After seven months without a car, I was

finally able to buy a war surplus jeep,

My brother, who had returned home ahead of me after the end of the

European war, had applied for the right as a veteran to purchase surplus

government equipment, but by the time his permit came through, he had managed

to get a used Plymouth, so no longer needed a surplus vehicle. He drove me down to Fort Lewis on the day of

the sale and helped me select the jeep in October of 1946. It cost $359. I had a lot of sinus trouble

that winter until my Dad helped me build an enclosure for it! Our second child

was born shortly after we acquired the jeep.

I had driven Marie to visit her parents and went on to the Renton plant

where I was working second shift at the Photo Template Unit there. I recall just begining work when I was called

by the receptionist who informed me that Marie had gone to the hospital and was

in labor. The jeep made a very fast trip

from Renton to the old Seattle General Hospital, and I did arrive before our

son Perry was born.

I was transfered to the Photo Unit after

several months of Photo Template work, and put to work microfilming drawings

from the engineering vault for preservation purposes. One day when the

scheduler had more assigments than photographers, she asked if I knew how to

use a camera. There were only about four

cameramen in the unit at that time. I said yes and was sent out with an 8x10

view camera to photograph testing of

mounts for a fifty-caliber machine gun at a firing range operated by

Pacific Car and Foundry in Renton. From

then on I no longer did microfilm. The

work was interesting, assignments included recording everything that the Boeing

Co. was involved with, including a new experimental jet bomber, the B-47, as

well as the Stratocruiser commercial airliner.

However, the pay was low, so when I learned a photographer was needed to

join a Boeing guided missile field test crew then at Alamogordo, New Mexico, I

applied and was transferred there. (A

so-called "Swamp Pay" bonus was added to the salary of personnel

working there. This was a great help in

paying off some debts we had accumulated.

Also, our eldest son, Steve, had developed asthma, and the climate

change was expected to be beneficial.)

In December of 1947, just before going to

Alamogordo, I photographed the first flight of the XB-47 from Boeing Field.

My jeep and I

beside a camera station used to photograph the first flight of the first US Air

Force jet-powered bomber, the XB-47, Dec. 1947.

At Alamogordo, I and two other

photographers recorded test data on experimental guided missiles being

developed for an Air Force contract. Missiles were flown down from Seattle and

fired on the test range near White Sands.

Werner Von Braun's group of German rocket scientists worked nearby at

the Army's White Sands Proving Ground.

Each time there was a firing of a Boeing GAPA,

(Ground-to-Air-Pilotless-Aircraft) we

set up and operated 21 separate data stations.

Some automatically recorded oscilloscope traces on rolls of photo paper,

some recorded telemetry data, some radar boresites and some were manned

stations using tracking cameras. My

station was one mile downrange from the launch pad so that I could film the

separation of the booster rockets from the second stage missile with a long

telephoto lens. There were sandbags

around my camera station and I wore a steel helmet. In those early days it was not uncommon for

rocket boosters to explode and rain down parts and fire on the desert. There were no tape recorders then, so

everything was recorded photographically.

After a year and a half at Alamogordo, I was reassigned to Seattle and

was promoted to Assistant Photo Unit Chief.

The company was expanding with production of the Stratocruiser

commercial airliner, B-47, B-50, and beginning work on the B-52 along with a

system of in-flight-refueling for military aircraft.

Our family returned to our little home which we had

rented out while we were in Alamogordo, and got busy building a new home

adjoining it. We were able to move in

about eighteen months later, in time for our third son, David, to join us

there.

Our home in October, 1956

It was an exciting time to be at Boeing

while so many inovations in aerospace technology were being developed. The Photo Unit grew with the company, until

we had about 100 people. In addition to covering events as mundane as award

ceremonies and executive portraits, we recorded engineering tests, including

wind tunnel work, provided slides and other materials to personnel making

presentations, did general record phototgraphy and occasionally went along on

flight tests to get pictrures of aircraft in flight. When motion pictures were needed we did

those. In the 1940's and early 1950's the company did

not have a complete motion picture production facility. We did the camera work and rough editing and

then carried the film to Hollywood for final editing and sound work. I performed that duty once in 1951 with a

highly classifiied progress report film on the B-47. While there I ran across a man who wanted to

sell his Auricon single-system sound camera at a very attractive price. I bought it and had it shipped home via air

express. For a period of time over the

next couple of years I did a few television commercials in my spare time and

made one feature length film for the volunteer firemen in the Richmond Beach

community where I lived. They used it

for several years showing it at local schools during fire prevention week. I had visions of going full-time in the

television market, but without the necessary capital and having by then a

fourth son, Brian, I decided there were not enough hours in the day to continue

with such a demanding sideline, and consequently sold the camera.

My former boss, Glenn Jones, was placed in

charge of a new Motion Picture Unit separating that segment of the work

from still photography and I became the

Photo Unit Chief. We made dye transfer

color prints prior to the availability of simpler processes. Our lab was one of

the first industrial photo labs to use color negative materials for in-house

color processing and printing. It was one of our goals to use the capabilities

of photography as an industrial tool wherever practical. For example, one of our photographers, Neil

Hare, was assigned to photograph structural testing of the B-52. The tests

gradually loaded the structure to the point of failure. Once this occurred, the

engineers often spent hours attempting to determine which part failed first and

triggered a split-second breakdown of the airframe structure. Neil suggested to the engineers that it might

be better to photograph the first part

to fail at the instant of failure instead of doing post mortem photos of broken

wreckage. Determining which part broke first invariably became a guessing game

after the fact. He was asked to try, so

with a few small strobe lights and a special inertia switch he made from a

telephone relay and a lead weight, he was able to demonstrate that an

unobserved rivet failure in the skin of a wing panel caused a major breakdown.

Our chief engineer was intrigued with the idea and wanted to be sure we devised

the best system possible to cover the entire structure during major testing not

yet done. As a consequence, I was sent on a whirwind tour to Rochester, Boston

and New York where to meet with experts at Eastman Kodak, Wollensak Optical,

and Graflex in Rochester. At Boston I

talked with Dr. Edgerton at MIT and personnel at the Edgerton, Germeshausen &Grier company. In

New York I met with Ascor Co. representatives, builders of large strobe

lighting equipment used to light

nightime sporting events, and with Schneider Optical. The experts didn't come up with anything

better than Neil's homemade inertia switch for triggering the cameras, but they

did have good suggestions for large-scale electronic flash lighting and were generally

helpful. This system was used

successfully in testing where the full sized structural model of theB-52 was

ultimately loaded to 118% above design load before failure.

Boeing became involved with space after

the Russian Sputnik was launched. The Seattle Division became the Aerospace

Division, with responsibilty for such programs as the Lunar Orbiter, Bomarc

missile defense system the Minuteman ICBM and development of the huge rocket

engines used for the manned landings on the moon. John Pennell, who had been my assistant

chief, went to the new Transport Division to head up another Photo Unit there.

When the Boeing Lunar Orbiter program was

mapping the moon to survey possible landing sites, the images were transmitted

by radio back to earth and recorded on rolls of 35mm film. NASA had released

some copies to the news media showing a picture of the earth taken from the

lunar orbit with part of the moon in the foreground. The reproduction was poor and the newsprint

reproduction made it worse.. The result

was that politicians began screaming that Boeing (Eastman Kodak had

responsibility for the actual camera system.) had done a lousy job and NASA was

threatening to take away the company's incentive award. (Government contracts negotiated at a fixed

fee included an incentive award for schedule and cost underruns.) One evening

as I was getting ready to leave for home after the end of regular working

hours, the Aerospace Division Manager, George Stoner, burst into my office with

a NASA Phd. in tow. They had the original film strips of the published picture

fixed to a sheet of plexiglass, and George was telling me to look at all the

detail in the film strips. He asked if

we could make a copy that might capture that

detail. Our night shift was at work

so I asked one of the men, Robert Winans, to put it in a vacuum frame and expose a print with a point source

light. I carried the wet and still

unwashed print to the pair waiting in the office. They were overjoyed and told me we had

probably saved the company a million dollar incentive award!

Our photo lab later reproduced the lunar

orbiter photos for NASA. It appeared that either the engineers had varied the

strength of the radio signals during transmission, or some other reason had

caused wide density variations in the film during transmission from the orbier

to earth. We devised a roll printer using a point source lamp with a variable

intensity and won a NASA contract to reproduce the moon photos.

Changes in company structure eventually

placed all photography in a new Services Division instead of being a part of

the Engineering organizations in the separate divisions. I did a study and published an internal

report recommending greater use of microfilm as opposed to blueprint copies of

engineering drawings. Digitizing the

drawings was not practical at the time. The scope of the company's operations

with multiple commercial models in production along with military contracts

made it difficult and expensive to keep production areas up to date with

drawing changes. Distribution of

multiple paper copies to manufacturing shop files sometimes took up to thirty

days. It was not uncommon to have parts

and assemblies scrapped or reworked because they were built from outdated

drawings. By distributing microfilm aperture cards to the files we were able to

reduce the flow time to three days or less. Drawings and data had to be

delivered to the company's customers as well. Most government contractual work

had used microfilm for many years, but with the exception of the 747, and

certain maintainance manuals, most airlines and Boeing's manufacturing areas

had not made active use of film. I was given the job of making the system work

companywide. It was a good example of using photography as an industrial tool.

Boeing computers were mostly kept at central locations under control of special

computer service personnel. We had to convince upper management that we needed

a designated computer to keep track of the drawings and their changes. It was called a "mini-computer",

but with its peripheral equipment it filled a large room. The greatest problem involved in making the

microfilm system work was convincing

people in other departments and airline customers to use it. There were about a hundred thousand people employed

at Boeing then, and at times I felt most of them resisted the idea. For more than a year I was involved in making

presentations to other departments and occasionally to airline customers. I had

a slide film presentation with a sound track made to show how the system worked

and its cost benefits. The conversion

was finally completed, and I was assigned a new job with responsibility for the

company's records management and storage operations, the company's historical

unit and did special assignments trouble-shooting compaints recieved by our

upper manager's office. I spent much of

my time driving between the various company locations and plants in the whole

Puget Sound area, from Auburn to Everett.

I had a desk at the Historical Unit in Plant II, another at the

Transport Division in Renton and one

more at the Records Facility in a large warehouse at Kent.

There were times when on special assignment

that I needed to write a memo quickly.

Fortunately there was a very capable lady at the records center who had

been the secretary for the vice president of engineering at the Transport

Division, Maynard Pennell, until his retirement. (He was considered the "father of the

707".) Margory Radke took dictation

over the phone and typed faster than I could talk. The memo with corrected

grammar was always ready for my signature before I could get back to the

office. It was her responsibility to maintain the records of company

stockholders and to send copies of the company's annual report and form 10k's

to requesters.

My

position with the company had changed considerably over the more than

thirty years I had been there, and I no longer enjoyed it as much as when I had

been involved with photography. My wife

and I had moved our family to Vashon Island in 1959, where we had purchased a

small waterfront lot and built a new home.

I began building a boat in my spare time and longed to get it finished.

I decided to take early retirement from Boeing as soon as I could see my way

clear financially. Our four sons were

all grown, married and moved away, and we had no mortgage. I left the company, July 1, 1979. I felt flattered when the grandaughter of

William E. Boeing (founder of the Boeing Company) and the director of the new

Seattle Museum of Flight took me to lunch when they heard I was leaving. Since

I had been managing the company's historical records unit they wanted me to

help with the museum, and I would have liked that, except for wanting to finish

my boat, and I did not want to continue commuting to Seattle.

I spent the next three years enjoying

retirement and completing the boat on the bulkhead at the beachfront below our

home. I had owned other smaller

sailboats and had been commodore of the local yacht club in 1964. One of the yacht club members, Dave Sweeney,

who was a small craft designer and had worked for Ed Monk in Seattle, designed

the boat for me. He did a great

job. Originally it was planned to be of

wood construction, but at his suggestion I changed to ferro-cement. Under power

its maximum speed was a bit over seven knots, but on a reach with a good wind

it was clocked above ten.

Marie and I are standing under the stern of the steel

and wire mesh frame work of the boat shortly before the cement was applied.

Begun in 1968, it took three years of spare time to

get the construction to this point. The

cement was added in 1971. It was not

ready to launch for another ten years.

Launching of the forty-foot ferro-cement

ketch, Starfire, from our home on the Burton

Peninsula in Quartermaster Harbor on Vashon Island, in June, 1981. The boat in its cradle, all 15 tons of it

including 10 tons of lead and iron ballast, was moved from the bulkhead on

rollers over heavy timbers. Then the

cribbing supporting the timbers under each end were removed and the process

repeated until the boat was positioned where the tide could float it out of the

cradle. I

obtained a

license from the U.S.Coast Guard to skipper passenger-carrying vessels of up to

fifty tons and conducted cruises in the San Juan Islands and Canada for several

years. I continued using the boat for pleasure after retiring from the charter

business and finally sold it in 1995. The effort and expense of maintainting it

eventually overcame the pleasure. The

boat was sold to a young Canadian and his wife who lived aboard it on the

Fraser River near Vancouver, and has since been sold again. It is, so far as I

know, still in Canadian waters.

obtained a

license from the U.S.Coast Guard to skipper passenger-carrying vessels of up to

fifty tons and conducted cruises in the San Juan Islands and Canada for several

years. I continued using the boat for pleasure after retiring from the charter

business and finally sold it in 1995. The effort and expense of maintainting it

eventually overcame the pleasure. The

boat was sold to a young Canadian and his wife who lived aboard it on the

Fraser River near Vancouver, and has since been sold again. It is, so far as I

know, still in Canadian waters.

Cruising the San Juan Islands in Washington State..

The Starfire at anchor beside our

Vashon home, 1986.

In 1994 we purchased a condominium in

north San Diego and now spend our winters there but return to Vashon Island in

summer. By early 1998 I realized photographic technology was passing me by, and

invested in a computer and a good quality film scanner. Since that time I have gone back to

photography for my own pleasure. I enjoy

using the computer to restore deteriorating old photos for relatives and

friends and to preserve my collection of wartime photos. I am a member of the Rancho Bernardo Camera

Club and regularly enter their competitions.

I now use a digital camera, and no longer have to buy film or wait for

photos to be processed!

On our San Diego patio.